Today’s post comes from Kalim Ahmed, a writer and open-source researcher who focuses on technology, policy and culture. Kalim explores whether the internet is homogenising how we communicate and how AI may affect this. As always, please let us know your thoughts.

New technologies shape how we communicate. The printing press spread literacy to the masses. The talkies did away with silent films. In the streaming era, songs have become shorter. One particular effect of new technologies is that they often introduce a degree of standardisation in the medium and homogenisation in the message. This influences how we come to experience and understand the world. Since this essay begins with the terms “medium” and “message”, it’s only fitting to turn to Canadian philosopher and media theorist Marshall McLuhan.

In his seminal 1964 work, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, McLuhan observed that nationalism was largely unknown in the Western world, until the printing press allowed people to encounter their mother tongue in a standardised form. This linguistic uniformity, he argued, helped to forge national identities and weaken older regional loyalties. Recognising this power, governments moved to regulate these technologies, out of a desire to cultivate a common culture and a fear for where a more hands-off approach may lead.

For example, McLuhan noted how some Arab countries banned the use of private headphones to ensure that radio listening remained a public, collective act. Similarly, the legal professor Lili Levi has described how the US Federal Communications Commission saw radio as serving a 'homogenizing and unifying social role’. In that spirit, it banned ‘propaganda stations’ focused on specific subcommunities and required broadcasters to cover controversial issues in a ‘balanced way’, prioritising a shared public understanding over the creative whims of producers.

In the digital era, most governments’ ability to regulate and shape media technologies in this way has diminished, even if their appetite for control has not. Unlike radio, the internet isn’t constrained by limited airwaves. It is abundant, accessible, and decentralised (a bit of a misnomer, but you get the point). Ironically, however, in the online world, the push towards ‘cultural sameness’ seems only to have intensified. But this time, it’s not top-down regulation that’s driving it - it’s individuals themselves, generating and consuming the same kinds of content, in a remarkably bottom-up fashion.

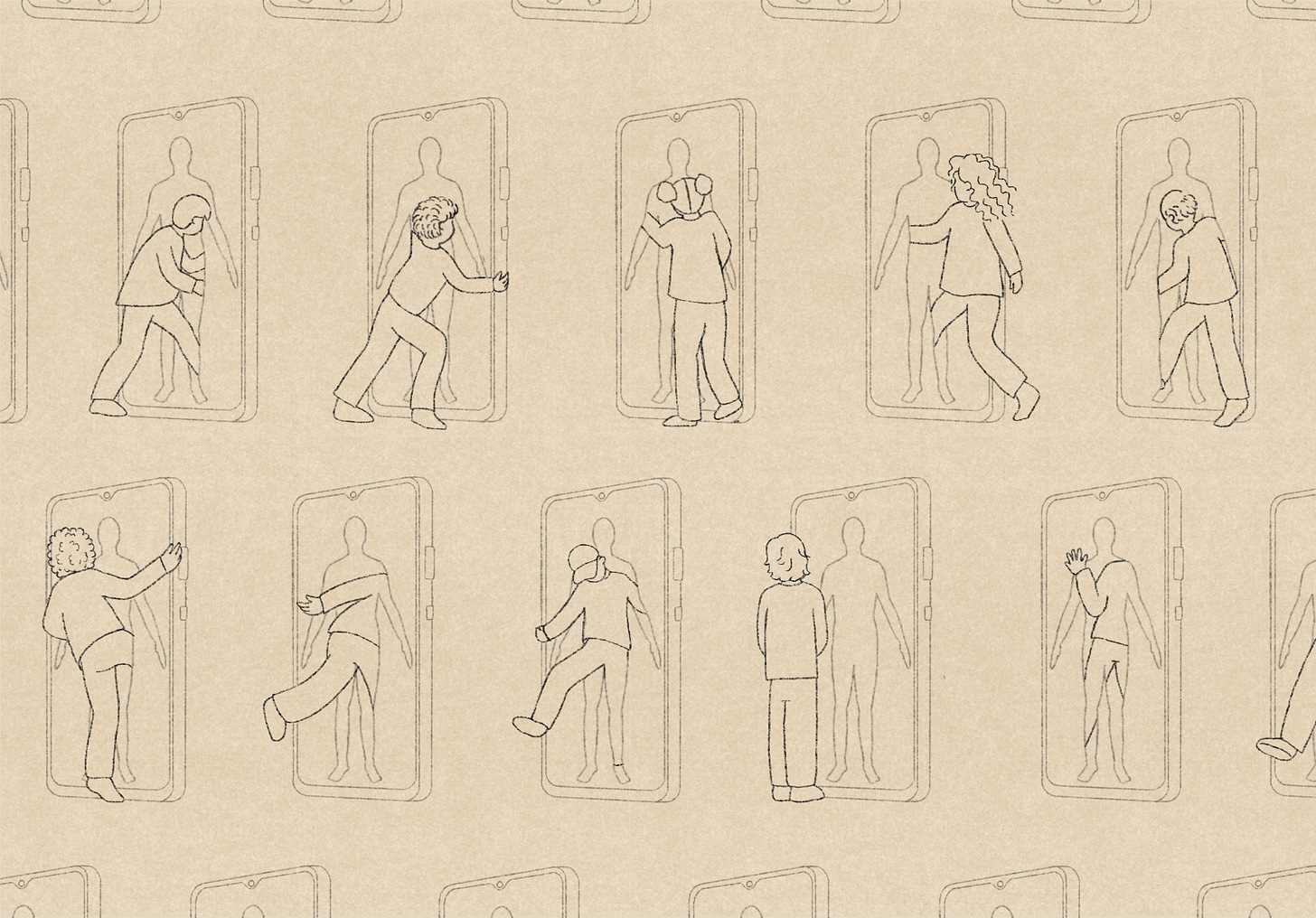

What is causing this push? For many, the separation between the online world and real life is collapsing. As people spend ever more time online, culture has begun to mould itself around the internet’s logic. Encouraged by recommender systems, which have tended to privilege popularity over diversity, we increasingly consume the same content, speak in the same idioms, and contribute to the same trends.

In his 2015 manifesto, The Transparency Society, philosopher and cultural theorist Byung-Chul Han called this condition the ‘digital panopticon’. Unlike Foucault’s silent, isolating surveillance, Han describes a world where individuals willingly perform their lives under the gaze of others. In other words, we’re not just watched, we’re performing for the watchers. We aestheticise our lives to meet the algorithmic standard. But as we do so, the boundaries of expression shrink. We speak, we share, we record - but we begin to sound eerily alike. Shakespeare saw this trend early when he wrote that “all the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.”

In our post-pandemic world, this stage has collapsed inward. There’s no need to wait for an audience and there is no intruder. We invite the phenomenon with open arms; the screen is enough. Platforms normalised the broadcasting of the self, first as an act of occasional performance, and now as a ritual. In such an environment, performance begets mimicry. We begin to replicate one another and our expressions become less about interiority and more about legibility - what will be seen, liked, or shared. Over time, this creates a loop of sameness, where individuality is shaped not by thought, but by visibility.

Not all content is homogenised equally

Most of us could recognise “internet speak” without being able to define it. Picture a “day in the life” vlog: the flat, affectless voiceover, the slick edits, a minimalist apartment in neutral tones. Curtains drawn back. Coffee brewed. Jog completed. Every moment tailored to project discipline, control, aspiration, and a soft, sterile affluence. Our protagonists exist in curated solitude. No friends or family appear. No noise, no clutter. Just productivity, aestheticised.

Influencers may have pioneered the template, especially during lockdowns, but everybody now performs it and the algorithms promote it. Internet speak extends to memes and catchphrases - those brief, hyper-referential fragments of culture that flood our feeds and vanish almost as quickly as they appear. Some linger longer than others - ”Catch me outside, how about that?” (2017), or “Pooja, what is this behaviour?” (2022), or “Very demure, very mindful” (2024) - but most dissolve into the endless feed before registering. It begins to resemble that infamous scene in A Clockwork Orange, where the protagonist is strapped in, eyes forced open, condemned to absorb whatever flashes on the screen. Only now, we do it to ourselves. Willingly.

The online world also shapes how we speak, or at least how we perform speech, offline. What becomes popular can affect our daily rhythms, accents, and verbal tics. In 2021, viral news reports suggested that American children had started speaking in vaguely British accents after extended exposure to Peppa Pig during the Covid-19 lockdown. The evidence for this was anecdotal, but it points to a larger truth - online culture is a powerful vehicle for exporting linguistic habits.

Consider the Valley Girl-style overuse of “like” as a filler word. I hypothesise that this can be traced, at least in part, to the fact that much of the technology that enabled self-broadcasting emerged in the US and so the linguistic ground was first occupied by native speakers who set the tone, cadence, and affective style. Everyone else simply adapted. The result is a speech pattern that feels breezy, casual, and emotionally flattened - the kind of tone that algorithms also seem to prefer.

If the “Catch me outside” girl is an exaggerated embodiment of this performative cadence, so too is the rise of “up talk”, or High Rising Terminal, where declarative sentences end with a questioning inflection. This phenomenon was once also associated with young women in Southern California, but has spread far beyond its origins, adopted by speakers across regions, genders, and class lines. Its rise is a reminder that platform-mediated speech is not only shaped by visibility but also by who gets seen and heard first.

This algorithmic conformity doesn’t stop at the content we express. It seeps into our physical surroundings. Today, whether you’re in New Delhi or Kathmandu, walking into a café increasingly feels like entering the same meticulously curated scene: exposed brick walls, high-contrast Edison bulbs, matte-black menu boards (now swapped for QR codes), and a menu of boba tea, matcha, or some trendy variation thereof. The furniture is distressed, the playlist is ambient and indie, and the vibe is always tuned to a soft, sterile version of authenticity. The banality of the internet’s lingua franca - minimalism, mindfulness, and a curated performance of taste - has spilt into the offline world, where it is shaping how and where we express ourselves.

Yet this cultural export is rarely reciprocal. How often do Western users adopt words or phrases from Indian English, say, “prepone,” for instance? The flow of influence remains largely unidirectional. We absorb the dominant voice, often unconsciously, while our own idioms and accents remain peripheral. This is not to say Indian-origin words haven’t entered the English lexicon: terms like “pariah” and “loot”, absorbed during colonial and pre-industrial periods, are now firmly embedded in our colloquial vocabulary. But these borrowings are historical artefacts, not reflective of contemporary cultural parity. This imbalance is also at the heart of concerns about large language models.

Enter LLMs

In 2024, researchers published an experiment in which they gave a very small number of participants access to an LLM and tasked them with coming up with creative ideas. They compared these ideas against those that participants generated when using a set of ‘creative inspiration’ cards from the artists Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt. The authors argued that, in aggregate, the LLM-based outputs were less “semantically diverse”.

The worry about LLMs and homogenisation goes something like this: LLMs are trained with similar architectures and data and will inevitably be somewhat biased as a representation of global culture. If people and organisations start to use multimodal LLMs, or agents based on them, across the cultural spaces, to help write newsletters, generate images or create music this will inevitably lead to more cultural homogenisation. The fear is perhaps best crystallised in a 2017 tweet by software engineer-turned-writer Chet Haase.

Today, Haase’s observation feels less like a joke and more like a thesis: LLMs will generate what is most palatable, most generic, and least likely to offend. The average will become aspirational. The edge, or the anomaly, that which is strange, specific, or difficult, will be quietly filtered out. Think GenericAI, not GenerativeAI. An engine of blandness. An algorithmic distillation of the already said. Or as K Allado-McDowell put it: “LLM base models are built to be mid”. Beneath all of it lies a deeper anxiety: culture was once filtered by institutions or gatekeepers, but now it is being flattened by machines. Sameness is the product.

Are these concerns legit?

Recently, the British newspaper The Guardian faced some challenges after using the word “gotten” - the North American past participle of “get” - in an opinion piece. In response, they reminded readers that two-thirds of them were based outside Britain and that their US desk aims to reflect different linguistic and cultural norms. It also pointed out that “gotten” wasn’t a recent American invention, but rather emerged in Middle and Early Modern English. Language, it said, isn’t a fortress. The defence is compelling, at least to me. Language is indeed dynamic; what feels foreign or jarring one day often becomes colloquial the next. It is normal for words like “chat,” “normies,” “looks maxxing,” or “zoomers” to begin as internet slang, fringe and unserious, and later become embedded in mainstream vocabulary.

One could also challenge the idea that culture has become more homogenised, as it has moved online. Indeed, you could argue the inverse. That the internet has enabled the creation and circulation of an unprecedented heterogeneity of content. Memes mutate hourly; aesthetics are born and buried within weeks; microcultures bloom and vanish on Discord, subreddits, and Substack. When I zoom out, I still observe a kind of creative inbreeding. Even when the topics are new, the formats feel recycled; the voices start to blend; everything feels just a little… templated. There may be more choice than ever before, but for most of us, most of the time, this potential seems largely untapped.

The argument that LLMs will inevitably make things worse, by churning out content from the middle of the bell curve, could also be challenged. AI is not deterministic. In theory at least, we get to choose what we optimise models for - accuracy, engagement, familiarity, safety, provocation or curiosity. These ideas have long existed in the realm of media theory - LLMs might be the first tools capable of realising them. Consider the world of science where practitioners worry about replacing the unorthodox, intuitive and serendipitous tendencies of humans with a more homogenous AI-based approach to research. Here, we already have counter examples — such as an effort that used AI to identify and amplify anomalies in massive datasets from Large Hadron Collider experiments. Are there other disruptive ideas out there, ready to be liberated by new kinds of LLM-enabled recommendation engines, semantic search, or generative media?

A deeper pushback is to question whether homogeneity is truly bad, or whether a certain amount of it may be necessary, or even beneficial. In conversations about culture, it certainly sounds bad. But maybe people need some amount of homogeneity, in order to free up our minds for more creative pursuits? Even if homogenisation is bad, it may be an inevitable cost to bear, in service of a greater good - globalisation. For centuries, this was defined by the movement of goods, capital, and people. Then the internet enabled the spread of information. And now AI will enable the spread of intelligence and the activities that rely on it. And like every previous wave, it will follow a pattern: diversity at the margins, conformity at the centre. In the early stages, choice will look like it's expanding. But over time, tastes will coalesce around the most exportable, the most scalable. And perhaps this is the inevitable price to pay for scaling connection. If we believe that globalisation, despite its faults and recent retrenchment, is a net good, are we willing to accept a steady drift toward uniformity as its cultural side effect?

What to do?

First, to get a handle on the challenge, we could measure if and how online culture is homogenising. A growing number of organisations have designed evaluations to assess the risks that AI poses, from hallucinations to cyber-attacks. But few have tried to evaluate the quality and diversity of online content, people’s engagement with it, and how this is changing in an AI world. Should we design new quantitative metrics of novelty or counterintuitiveness? Should we invest in ethnographic studies about how LLMs are reshaping cultural reference points? More important than the measurement technique: What does good look like here?

Second, if the concern is a global flattening, then governments could take their nascent ‘Sovereign AI’ programmes and apply them to cultural ends. Few would advocate returning to a world where governments dictate cultural content. But more would likely support the need to digitise and protect local languages, books, and history. Take my own home state in Northeast India. My native tongue - an oral language with scant written documentation - remains virtually absent from digital corpora, as do many others. A recent, mildly absurd anecdote illustrates the issue. An Indian food delivery app used AI to visually auto-render a traditional eastern Indian dish - Aloo Bhaja - a crispy, golden heap of shredded fried potato. What the app showed instead was a sandwich-like creation that was completely alien to the dish. Such exclusions cannot be resolved by AI alone. We need structural interventions.

Third, AI labs could empower individuals to personalise their nascent AI assistants. Users can already toggle the ‘temperature’ of their LLMs’ outputs. Moving forward, they could share more nuanced instructions, context, and feedback about what they want. Equipped with long-form memory, these assistants could create ‘belief graphs’ for what they think users want and periodically check that this is correct. This could offer the kinds of personalisation that has long been promised online, but rarely delivered. Done well, this should provide a healthy buffer against homogenisation, not least since AI agents will increasingly communicate with each other, and so more personalised agents should lead to less homogenous outcomes.

This also raises a question about whether the homogeneity critique is yesterday’s problem, and whether tomorrow’s is over-personalisation. The internet is already shifting from the public to the personal. Those living under the same roof now watch their own content on their own devices. Social media executives note how people are communicating less on public feeds and more in private chat groups. New LLM assistants could personalise people’s online experience even more. Against this backdrop, the primary concern may shift from a surfeit of homogenous culture to a lack of any shared culture at all.

To offset this, some practitioners hope to develop recommender systems that can support both shared cultural experiences and individual diversity. But what is the user themself, worried about homogeneity on one hand and over-personalisation on the other, to do? One habit you pick up as a writer is learning to sit with the official version of events for a while, whether you’re in a war zone or watching a product reveal. It may seem tedious, but there’s a skill in parsing what’s said and what’s being left unsaid. You read the press release to read between the lines, to ask not just what is being communicated, but why now, and to whom. During the recent flare-up between India and Pakistan, I found myself with little to offer the public beyond a simple plea: add friction to your life. Not because slowness is inherently virtuous, but because the flood of unverified video and hyperpartisan content overwhelmed our attention. There was no shared anchor. It was just motion and noise.

Edward Murrow, during the height of the Cold War, warned that television was being numbed by commercialism and cowardice. In his now-famous “wires and lights in a box” speech, he lamented that the screen, instead of informing and elevating the public, had become a source of confusion, distraction, and spectacle. What he feared about television, we now live through daily online, only the feed is faster, the wires are invisible, and the box is always on and in our hands. With AI, the trade-off may be even more profound. Retaining some friction is not just an aesthetic choice; it is a necessary strategy for navigating what comes next.

___________

Thanks to Conor Griffin, Harry Law and Arianna Manzini for feedback. As with all pieces you read here, it’s the personal views of the authors.

Top stuff

Thank you for this thought-provoking piece – it invites disagreement in the best possible way.

Still, I sense a structural issue: observations morph into explanations, quotes masquerade as evidence. Take McLuhan’s claim that nationalism emerged with the printing press – a neat idea, but historically reductive. It sidesteps the military, bureaucratic, and linguistic machinery of absolutist states that actively forged national identity long before mass literacy.

This tendency recurs: technology’s influence is overstated, while the human impulse to imitate – to belong – is curiously underplayed. Hairstyles in the ‘50s, Bogart’s signature slouch, feuilleton phraseology – all precede TikTok. Technology amplifies imitation, but doesn’t invent it.

The “we” in the essay remains elusive. Who exactly are “we,” when I live in a small town with residents from over a hundred nations? And who, precisely, is the “dominant voice,” when our media use is increasingly fragmented?

The idea of fighting homogenisation with “quantitative metrics of novelty” sounds oddly self-defeating – a standardisation of deviation, if you will.

In the end, many of the proposed solutions reminded me of an old Volkswagen slogan: Individuality. Factory-installed. The user is cast as consumer; responsibility outsourced to tech – even for the erosion of shared culture.

That said, reading your piece – and interrogating it with the help of a language model – became a curious little process of discovery: an oddly old-fashioned, quietly contemporary dialogue. For that, my sincere thanks.