This post introduces the AI Policy Atlas, a rough attempt to sketch out the different topics that AI policy practitioners need to understand.

The landscape of AI policy is vast, from worries about abusive imagery to concerns that governments are not making enough use of AI. The temptation to discuss a specific topic of interest obscures a more basic question: what exactly is ‘AI policy’?

A glance at governments’ priorities provides some answers. Policymakers in the UK, US, Japan, and Canada are launching new AI Safety Institutes, with more countries likely to follow. The EU is shifting its attention from passing, to implementing, the EU AI Act. Singapore is developing a sandbox to boost small businesses’ access to AI tools. Policy teams in AI companies feed into these efforts, while also designing their companies’ own internal AI policies, such as whether and how they should open-source their models. To navigate this web of activity, AI policy practitioners must develop opinions on many interconnected topics, from how much to invest in technical mitigations, such as watermarking, to how much schools should enable or restrain access to AI tools.

Introducing the AI Policy Atlas

In this article, I map this sprawling territory of topics that AI policy practitioners need to understand to do their job well. I define ‘policy’ as both public policy and AI companies’ internal policies. By public policies, I mean the decisions and actions that policymakers can take on AI, including agenda setting; the design, adoption, or removal of specific policy instruments, such as regulations and taxes; as well as other levers at governments’ disposal, from research funding to procurement. By internal policies, I mean the decisions and actions that companies take to try to develop AI responsibly, or in line with society’s values, needs and expectations. Inaction is also a policy.

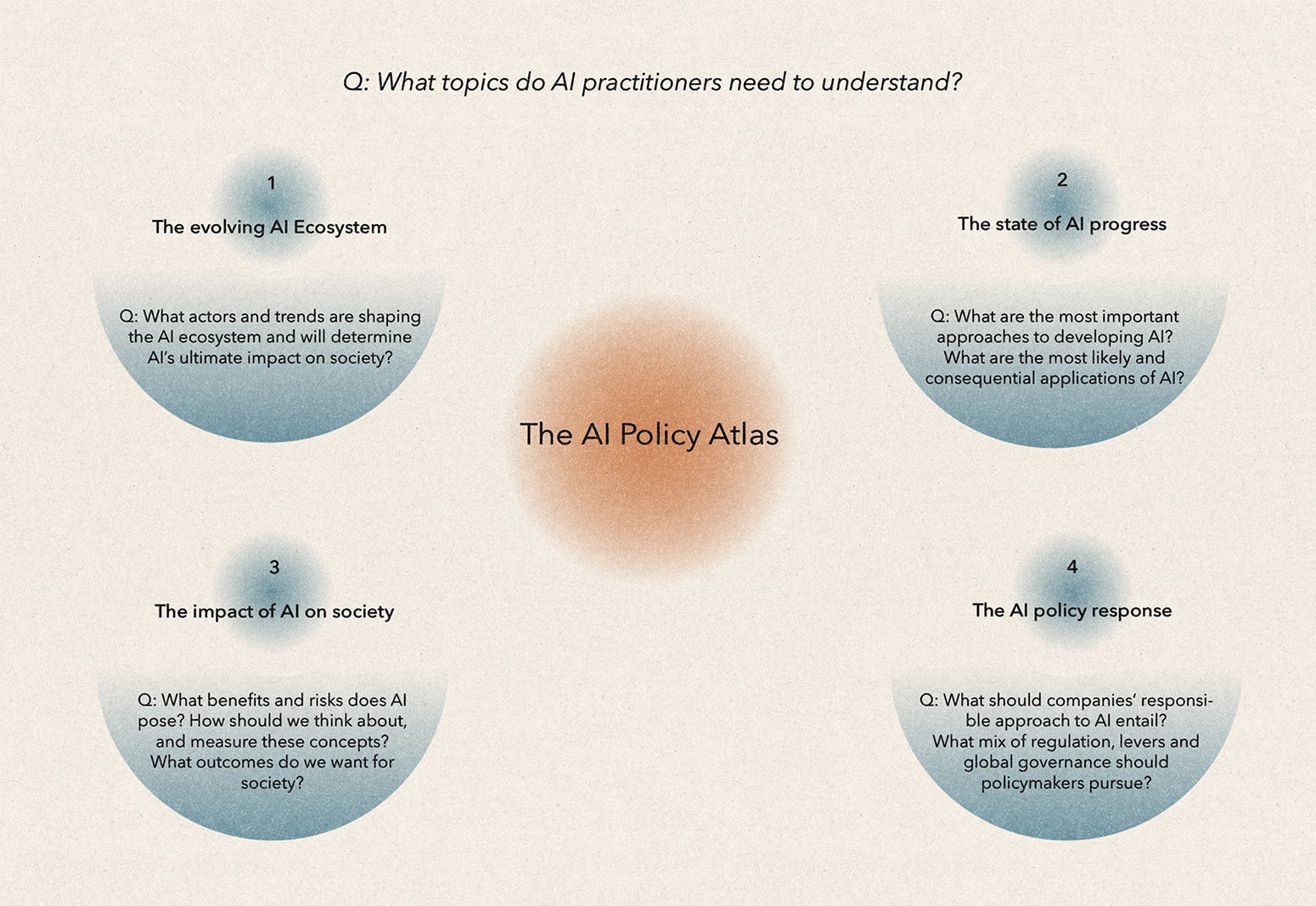

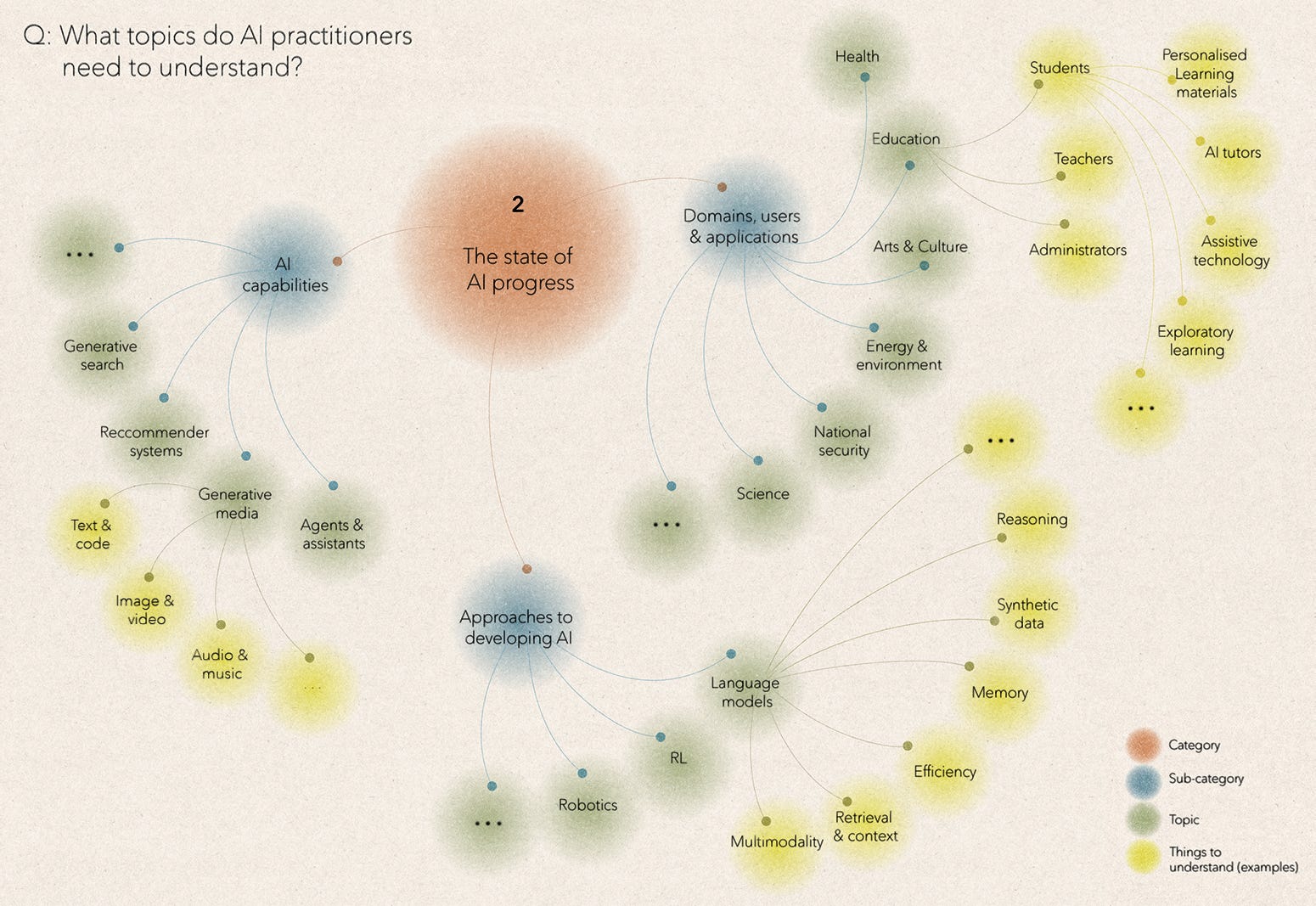

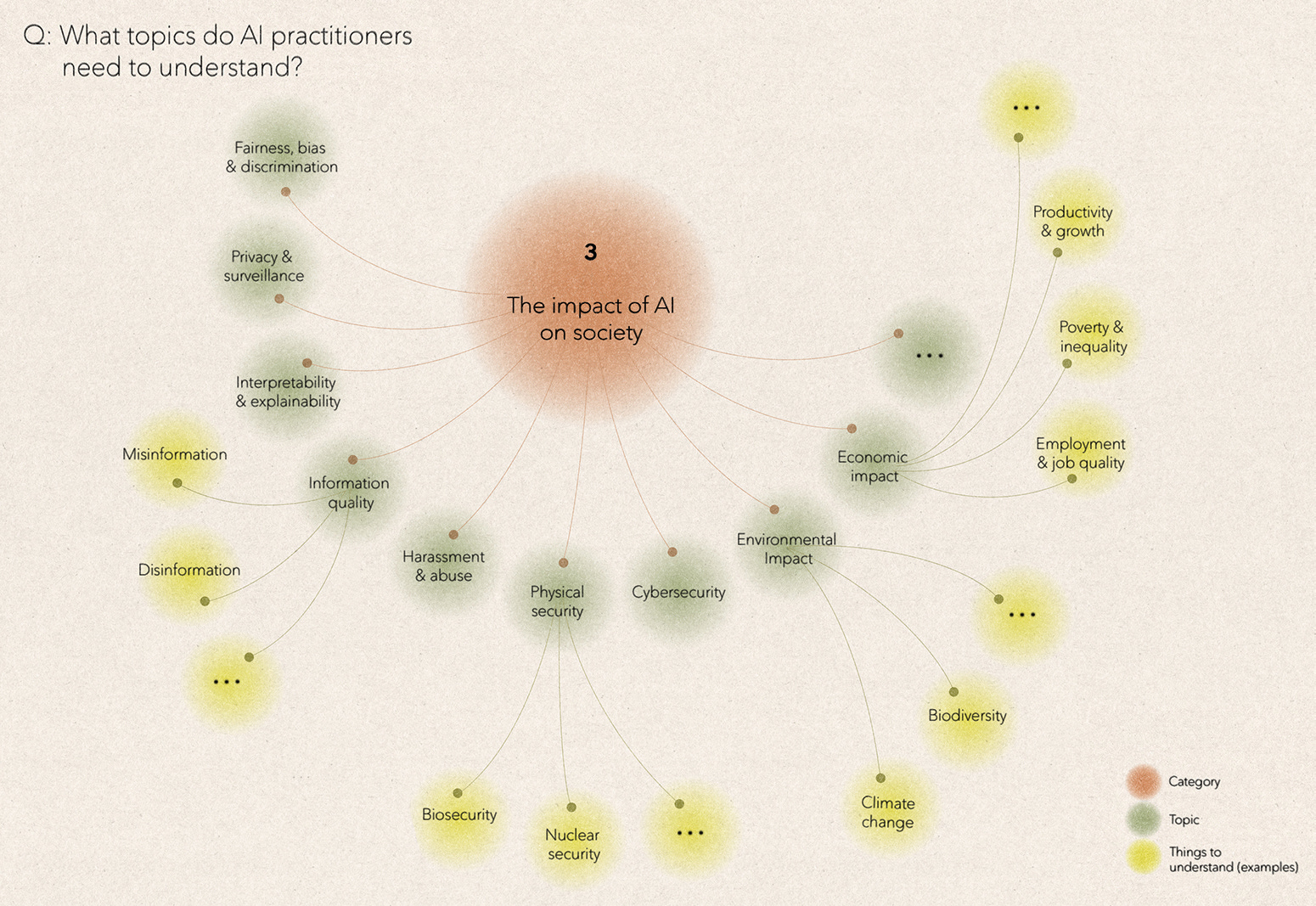

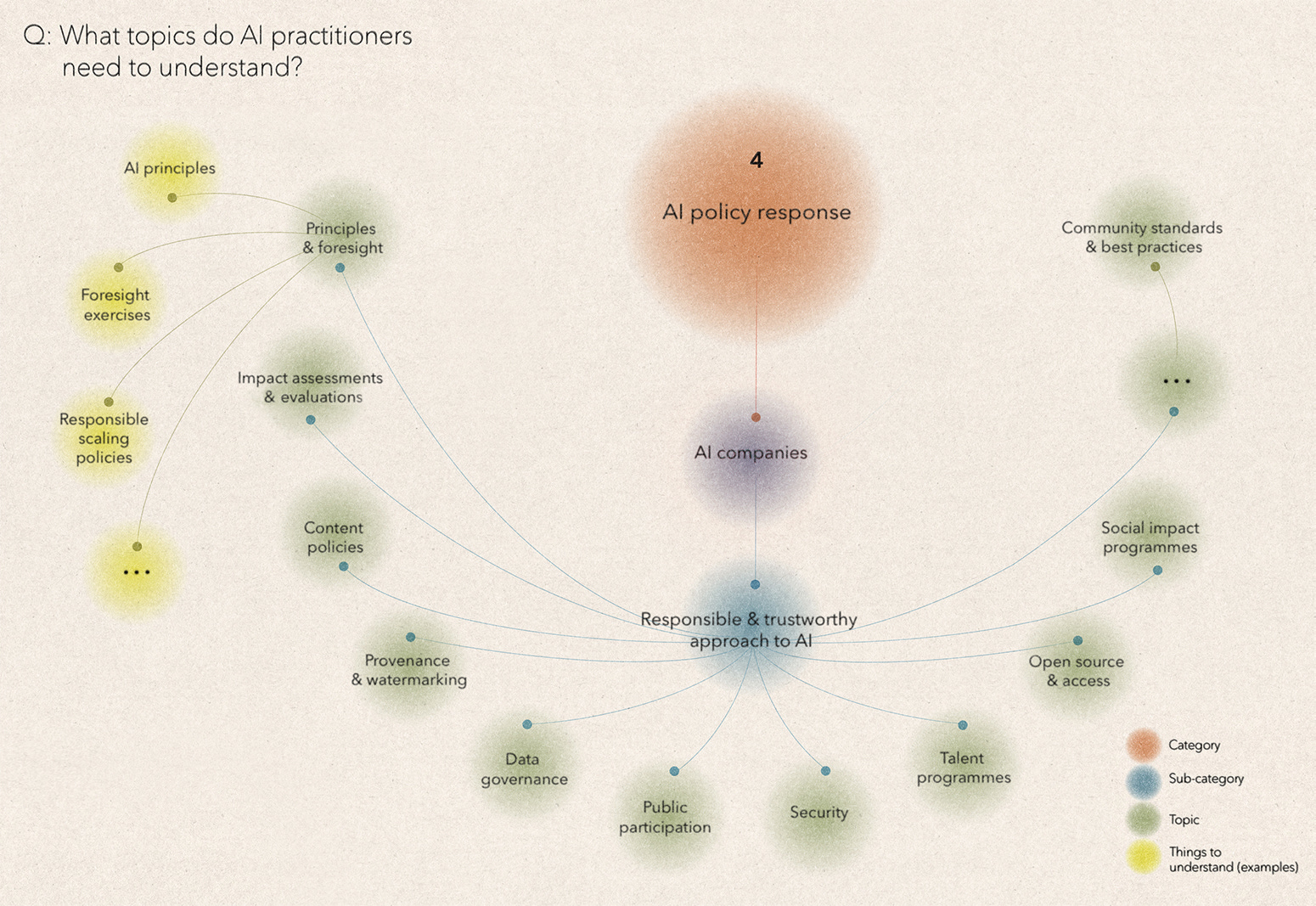

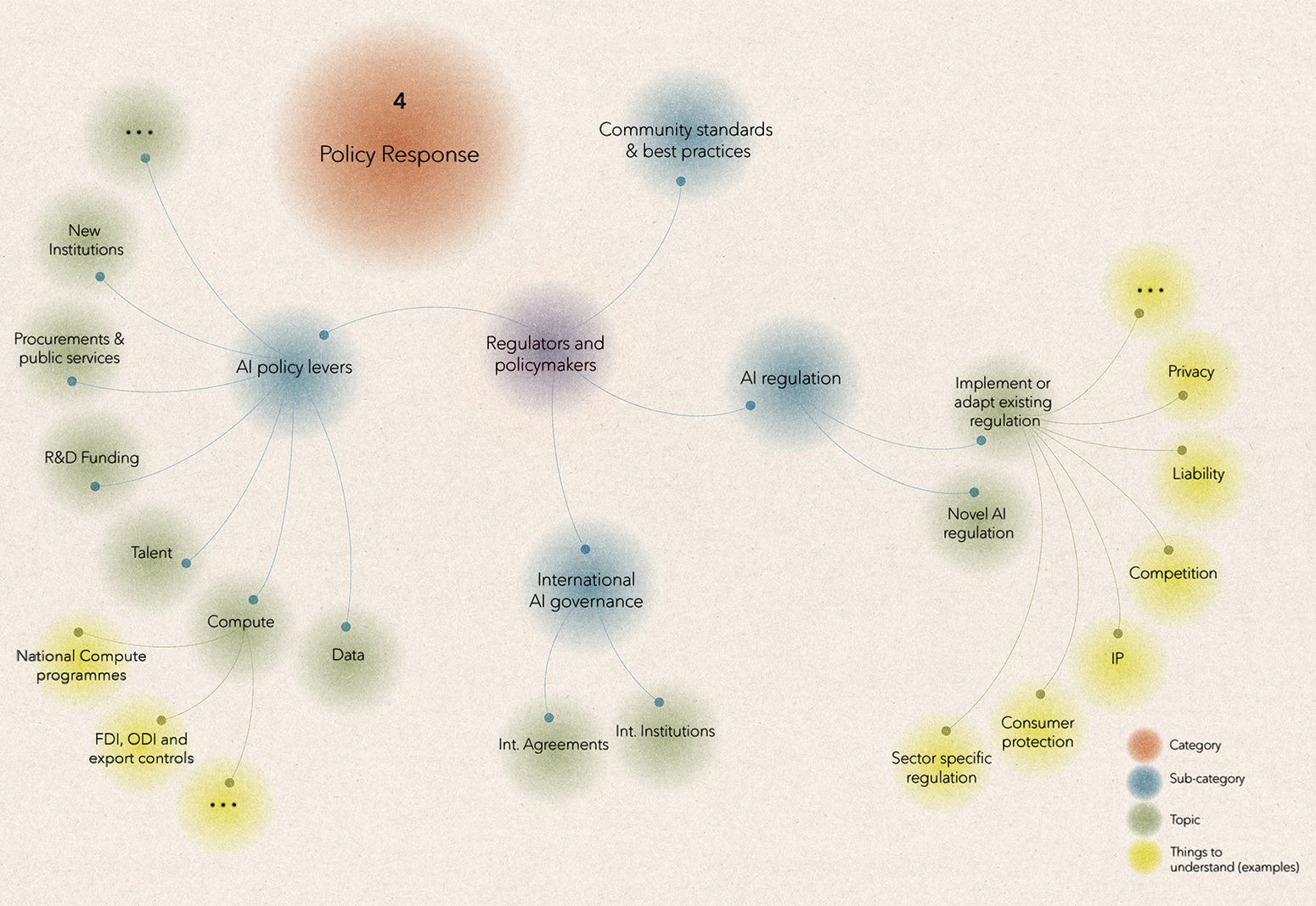

My Atlas has four categories that policy practitioners need to understand: (1) the evolving AI ecosystem; (2) the state of AI progress; (3) the potential impact of AI on society; and (4) the policy response.

The Policy Atlas has many limitations, which I describe at the end. But I hope that it can help AI policy teams on several fronts:

Reassurance: If you find yourself working on standards for AI data enrichment one day, before pirouetting into discussions about AI biology the next, you may feel like the world of AI policy is infinite and disjointed. I hope to provide reassurance that there is a finite body of topics that agglomerate productively over time.

Topic prioritisation: It's hard for policy teams to actively focus on some AI policy topics over others, and so prioritisation often happens passively by responding to requests. Or by focussing on what is most visible or tractable. Mapping AI policy topics can be a useful forcing function to consider if you are over or under-prioritising certain topics.

Access to expertise: It is impossible for AI policy teams to have deep expertise in all or even most of these topics. The Atlas is a call to widen the diversity of participants in AI policy discussions, to include everybody from researchers working on mechanistic interpretability to security specialists working on secure research environments.

Below, I introduce a brief sample of topics from the Atlas and explain why AI policy practitioners need to understand them.

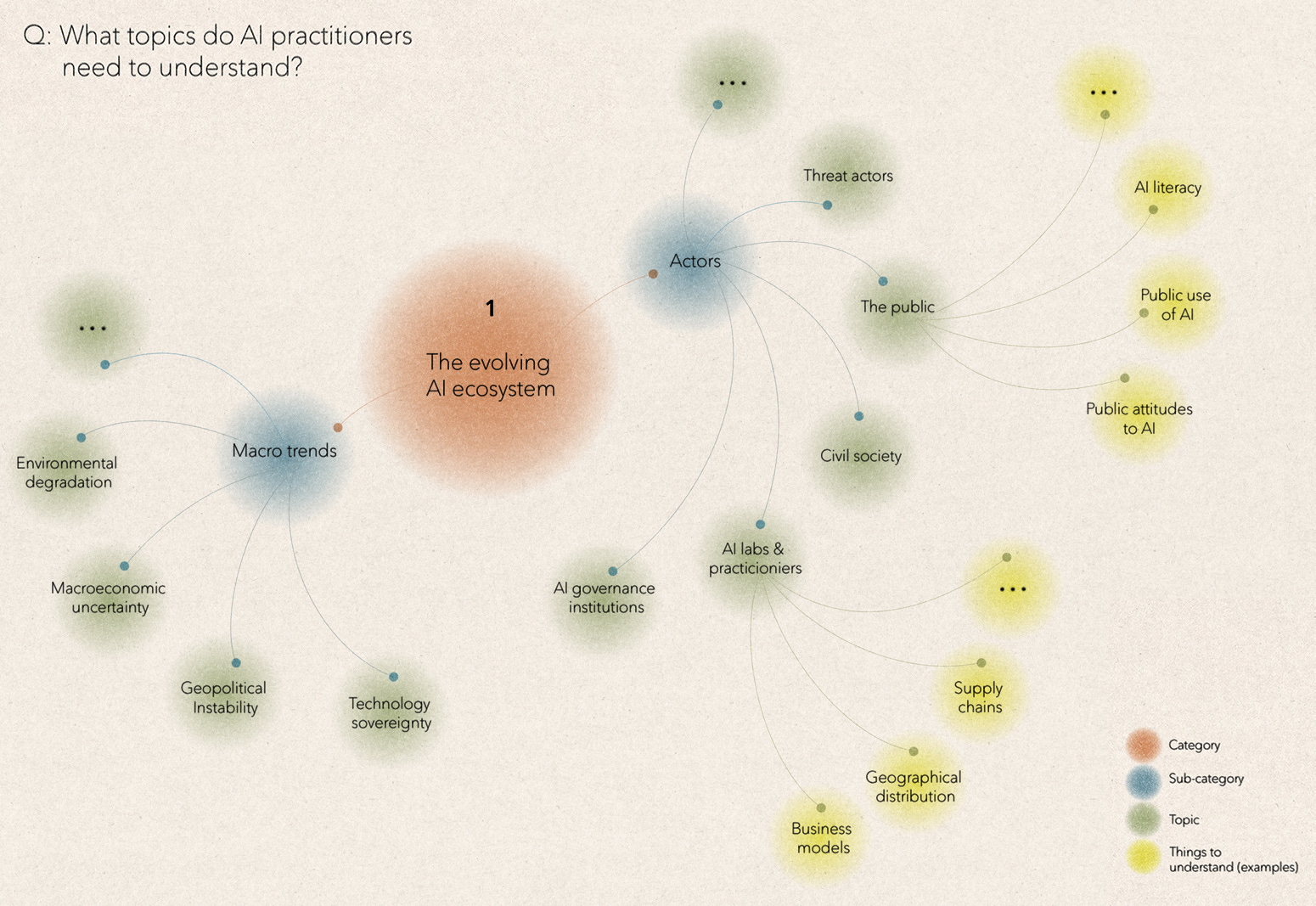

Category 1: The evolving AI ecosystem

In category one, we want to understand the set of actors that will most shape AI’s impact on society. The AI ecosystem is in flux. Over the past five years, a wave of AI startups has emerged. Some, like Anthropic, Mistral, or Cohere are developing large AI models from the ground up. Others are developing narrow applications, such as code assistants or protein design applications. A new supply chain is also emerging. Startups like Groq or Scale are providing AI developers with the picks and shovels, or chips and data, that they need. Other startups, like Together, function as market intermediaries, allowing product builders to pick and choose from different AI models. This evolving ecosystem challenges simplistic splits between AI ‘developers’ and ‘users’ and will have policy implications, for example, when it comes to assigning responsibility for carrying out AI safety evaluations or determining where liability falls.

We also need to understand how AI developers differ. Many AI policy discussions implicitly focus on business-to-consumer AI products, like chatbots or image generation tools. This is natural. These tools tend to be (somewhat) free, easy-to-use, and very memeable. Metrics on web visits, app downloads and subscriber numbers clearly show their uptake. In contrast, many B2B or B2G AI use cases take place behind closed doors, often in seemingly staid areas, such as document summarisation. This leads to a partial picture about how AI is diffusing across society, and an over-focus on B2C AI application in the resulting policy discussion. For example, without a good picture of how AI is diffusing across society, how do we know where the greatest cybersecurity risks lie?

Beyond understanding the organisations developing and deploying AI, we also need to understand the flow and make-up of individual AI practitioners, and the accompanying policy questions. For example, to what extent should we be worried about ‘AI brain drain’ from academia to the private sector, versus being reassured that the industry wants to hire PhD graduates—something that is not true of every field? To what extent should we be worried about more traditional AI brain drain —i.e. practitioners leaving their home countries to work in a small number of AI hotspots? Or should we instead worry about the potential ending of this global migration? As AI shifts from the lab to real-world deployment, a further question is whether governments and AI companies should be training different kinds of AI practitioners, perhaps shifting away from PhDs towards more targeted engineering and data curation qualifications?

As AI deployment grows, the public will also become a more important actor in AI policy debates. This will require a clear model for what exactly we mean by ‘public attitudes to AI’, how to measure it, and what AI companies and policymakers should do in response to it. For example, in the UK, a majority of the public claims to support applications that many AI practitioners take issue with, such as predictive policing and AI-enabled border control - although this support drops among people who are more likely to be negatively affected by these applications. Does this mean that AI companies should expand AI literacy programmes to explain the risks posed by these applications? Or should they more deeply question what applications they oppose?

Such questions highlight that we can't study actors in isolation. We also need to understand the wider macro trends that shape how these actors think and act on AI. For example, in recent years, the growing tension between the US and China has had a clear knock-on effect on AI policy, via export controls on chips. Similarly, the return of industrial policy to the West has encouraged governments to support local AI champions. What other macro trends - war? climate change? demographic shifts? - will most shape the next five years of AI?

Category 2: The state of AI progress

In category two, we want to understand the types of AI that are most likely to enter the world. There are inevitable limits to what can be done here, given the deluge of papers, products and APIs that AI labs are releasing. But to ground their work, policy practitioners need to stay abreast of key points of inflection and uncertainty.

We can start by identifying emerging and diverging approaches to developing AI systems. For example, the EU’s 2020 White Paper on AI laid the groundwork for the AI Act, but was published before OpenAI’s GPT-3 paper, and the subsequent emergence of large language models as a dominant paradigm. Early iterations of the Act classified AI applications into discrete buckets, based on their relative perceived risk, with corresponding obligations for developers and deployers. The emergence of LLMs, a general-purpose AI system that could be deployed across many applications, challenged the Act’s approach, prompting a rethink.

Paradigmatic shifts of the LLM variety are rare, but today’s practitioners are exploring various approaches to AI that could shape the optimal policy response. For example, to what extent should policymakers and AI labs expect research in mechanistic interpretability, machine unlearning, synthetic data, or fine-tuning to mitigate risks posed by AI to safety, privacy, and fairness? Or to what extent will growing efforts to merge large AI models with robotics succeed? And how might this change the jobs that are most likely to be affected by AI, as well as broader public perceptions of AI, and the policy response required?

We also need to be able to monitor the most consequential capabilities that AI systems might have. There are gaps in how we evaluate AI systems, which make it difficult to determine, or even describe, their capabilities. However, some capabilities jump out as particularly relevant. These include those where near-term step jumps are plausible, such as the ability of AI agents to execute workflows; the ability ofAI systems to do novel things, such as predicting diseases from retinal images, rather than just speeding up things that humans already do (the dividing line is fuzzy); AI capabilities that are likely to be misused by humans, such as emotion analysis; and AI capabilities that may be intrinsically dangerous, irrespective of how humans use them, such as deception.

Moving beyond AI capabilities, the policy response to AI will largely be determined by how people use specific applications. Today, this debate often starts by noting progress in a specific AI capability like music generation and extrapolating out to grand declarations about its likely effect on the music industry. A better approach is to start by better understanding the domain or industry in question. For example, if we want to think usefully about AI in education, we could start by clarifying the evolving function(s) that education should serve, such as preparing students for the labour market or helping to integrate them into society, and the extent to which it succeeds at this. We could clarify the specific obstacles that AI could help to address, which may lead us to use cases, like AI tutors. At this point, we could ground ourselves by learning from past efforts to apply digital technology to education, many of which have underwhelmed and explore how today’s AI tools could do differently.

Across domains, whether in finance, biology or the arts, the use cases for AI will look very different, and whether they get adopted at scale, or not, will depend on an array of factors, from sector-specific regulation to AI’s synchronicity with other technologies. One thing we can say with high confidence is that many of the most impactful AI use cases - e.g. weather forecasting - are unlikely to be prominent in current AI policy debates.

Category 3: The impact of AI on society

In category three, we want to understand the benefits and risks that AI poses to society. There are many ways to classify these impacts. Risk-focussed discussions often distinguish between discrete AI incidents, both intentional and accidental, and slow-burning societal impacts that may only become clear over time. Other AI risk taxonomies distinguish AI harms that are already occurring, or are very likely to occur soon, from longer-term risks. Conversely, despite rampant AI boosterism, there is very little, substantive, policy discussion on the benefits that AI may bring to society.

There are also fundamental challenges with the risks vs benefits framing. The most obvious is AI’s inherent dual-use nature. In areas like cybersecurity, we can quickly point to things that we do want to happen - organisations having better AI-based vulnerability discovery - and things that we don’t - threat actors having better AI-based vulnerability discovery. Even in areas like fairness, privacy, or explainability, where AI is primarily spoken about as a risk, there are clear potential benefits. For example, there are inspiring examples of mechanistic explainability research and lists of open research problems to tackle. AI models are also inherently more accessible to study than human brains. There is early evidence that by studying how AI models learn we can expand human knowledge, for example, by discovering novel chess moves from AI systems.

A deeper challenge is that we often cannot agree on the ideal outcome for society. For example, when it comes to biosecurity: do we want large language models to be able to provide accurate answers to detailed, technical, virology questions? Presumably ‘yes’ in the hands of certain actors, but ‘no’ in the hands of others. But can we reliably decide who is who? How?

In other areas, people fundamentally disagree about AI’s likely impact, and the challenge for policy practitioners is to design, support and interpret evaluations that bring these disparate views together. For example, when it comes to AI’s potential impact on climate change, most discussions (and evaluations) focus on the amount of power used to train ever-larger language models and the resulting effects on emissions. However, these emissions will likely be swamped by the positive or negative downstream effects that arise when people begin to use AI at scale - e.g. optimising grids - even if such impacts take time to materialise.

Similarly, if we consider ‘information quality’, there is rightly concern in 2024 about AI-based disinformation and election interference. However, consequential examples are rare, albeit likely increasing, and there is reasonable scepticism about how much any content, AI-generated or otherwise, actually changes most individuals’ minds. As outlined by Eric Hoel, a bigger challenge may be the rise in low-quality AI-generated content, even if such content is not necessarily false (misinformation), or intended to mislead (disinformation).

On the other hand, AI may also help to improve the quality of information, or help people to access higher-quality information, acting as a sort of spam filter + content curator 2.0. The World Bank and others have devised techniques to quantify how society is maintaining traditional public goods, like clean air, fresh water, and forests, as well as how accessible these resources are to the public. If we could devise similar techniques to measure high-quality digital information, or the digital commons, might AI help provide better access to it?

Category 4: The policy response

In category four, we turn to the AI policy response. I focus first on AI companies, and then policymakers, but naturally many of these policies may be led by, or delivered with, partners from across civil society, academia, and elsewhere.

Part A: AI companies’ internal policies

When I speak about AI companies' internal policies, I refer to the decisions and actions that companies take to develop and deploy AI responsibly, or in line with society’s values, needs and expectations. There can be healthy scepticism about such efforts, but responsible AI is also a more concrete concept than is often assumed, building on decades of work in the fields of responsible research and innovation and technology assessment, where practitioners sought to anticipate, influence, and control the development of emerging technologies, from GMOs to nuclear power. Increasingly, we can point to a clear set of activities that organisations that develop consequential AI systems may be expected to carry out, from robust data governance and security, to foresight exercises and watermarking.

One challenge for AI companies is working out how to prioritise their time and resources, across these efforts. For example, the AI community has traditionally evaluated safety and ethics risks from AI systems using (semi-) automated, dataset-driven techniques. As outlined in a paper by Laura Weidinger and colleagues this has come at the neglect of other ways to evaluate AI systems, such as evaluations that study how AI applications have actually affected society, post-deployment. When it comes to improving their evaluations, AI companies face a range of questions, including: What risk/benefit/impact(s) to focus on? How much to focus on new evaluations vs building the infrastructure to execute existing evaluations? How to best work with external partners, including in government? How to interpret the results and what constitutes ‘safe enough’?

Crucially, the concept of responsible AI, like its antecedents, does not just only focus on identifying and mitigating risks, but also aims to identify, accelerate, and better distribute benefits from AI. A key focus is identifying potential market failures, where beneficial AI solutions may not get developed, or may not reach those who need them. In pharmaceuticals, we see many examples of such failures - e.g. neglected tropical diseases - as well as public-private-partnerships to address them. These efforts are supported by a mixture of ‘push’ (e.g. grant funding) and ‘pull’ schemes (e.g. advance market commitments) from the public and private sectors. What is the equivalent for future AI market failures?

Part B: Governments’ public policies

When we turn to AI public policy, many discussions revolve around whether to regulate AI, via new legislation, enabling acts, and voluntary guidelines. Of course, much of AI is already regulated, via existing privacy, consumer protection and industry-specific regulations. As a result, the bigger challenge can be working out how to interpret and implement these regulations, and whether there are gaps to address or barriers to remove. There is also more novel AI regulation being passed than is sometimes realised, for example at the state level in the US, where a growing number of laws now ban certain deepfakes. In other cases, as with liability law in the EU, policymakers are both adapting existing regulations to account for AI and scoping novel regulation that are specific to AI.

What is often missing from this hive of activity is a debate about whether we need to fundamentally rethink some foundational types of regulation, for the AI era. For example, do privacy regulations need to expand beyond restricting personal data collection in order to unlock new AI applications or to respond to some developers’ claims to be able to infer sensitive individual attributes? What is a user’s responsibility to oversee an agent’s actions, and how does this intersect with the responsibilities of the system's deployers, or other actors in the supply chain? How do sector-specific regulations apply to AI agents operating across different sectors?

Beyond regulation, policymakers have a broad set of levers to shape how AI is developed, or who develops it. They can target the key inputs to modern AI systems - compute, data, and talent. Policymakers have already passed programmes, such as the National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource to widen academic access to compute, to try to incentivise beneficial AI applications. In the other direction, policymakers have used compute to monitor, restrain or control AI activity, as exemplified by the US-led restrictions on the export of chips to China, and by the 2023 US Executive Order, which imposed obligations on developers of AI models above a certain compute threshold. Lots of more speculative ideas exist, such as designing new types of chips with in-built controls. Policymakers could also focus on other levers, such as data, for example by trying to create more public interest datasets, like Protein Data Bank, to unlock more transformative AI applications, like AlphaFold.

The AI Policy Atlas: caveats and limitations

I don’t cover every topic: As indicated by the empty ‘...’ boxes in my graphics, the Atlas does not cover every AI policy topic. It could extend out much further, perhaps forever. There are many domains where you could apply AI and topics such as fairness, bias and discrimination have many sub-topics.

I cover too many topics: My goal is not to suggest that AI policy teams or individuals need to understand each of the topics in the Atlas. Rather by creating your own AI Policy Atlas, you can decide where you are best placed to contribute, where you need to rely on external expertise, and where you need to avoid getting distracted.

The topics are not discrete: People do not meet in separate policy rooms to discuss each of these topics. Rather, the important discussions often come at the intersections where the topics meet. For example: what types of evaluations should we design to understand the future impact of AI agents on employment outcomes in industry x?

I use the term ‘policy’ very loosely: My conceptualisation of ‘policy’ overlaps with other concepts, particularly ‘governance’, but also, in places, with AI ‘ethics’ ‘safety’, ‘responsibility’, and ‘compliance’. The idea is to bring together different practitioners working on the same topics and reduce duplication.

If you have thoughts on how to improve the Atlas or if you are doing interesting work on one of these topics, please get in touch at aipolicyperspectives@gmail.com.

Thanks to Harry Law, Sébastien Krier, Jennifer Beroshi, and Nicklas Lundblad for comments.

Interesting article. I am surprised by the omission of “human rights” though. I understand “Atlas does not cover every AI policy topic” but HRs are foundational for AI policy…