Book review: Inspectors for Peace

Inspectors for Peace: A History of the International Atomic Energy Agency by Elisabeth Roehrlich

We’re expanding AI Policy Perspectives to include essays, book reviews, landscape analyses, and more (you can read a full breakdown of the new types of content on our About page). To kick things off, we’re starting with a review of Elisabeth Roehrlich’s Inspectors for Peace––a must-read for anyone interested in understanding the IAEA. This review is written in a personal capacity by Harry Law, an Ethics and Policy Researcher at Google DeepMind.

Elisabeth Roehrlich’s Inspectors for Peace begins in 1974 with the story of two inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The book recounts an episode in which the pair—who were in India to review the country’s nuclear capabilities—were caught off-guard by news of a ‘peaceful nuclear explosion’ test. Known as the ‘Smiling Buddha’ incident, the experiment was made possible thanks to starting material for the plutonium provided by Canada and a reactor moderator, heavy water, supplied by the United States. The rub, however, was that these elements were supplied on the basis that they would be used solely for peaceful purposes.

The incident sets the backdrop for the core argument of the book: the IAEA’s ‘dual mandate’, which enabled the transfer of peaceful nuclear technology whilst also seeking to curtail its use for military purposes, both contributed to the proliferation of nuclear weapons and secured buy-in for the organisation’s anti-proliferation agenda. As Roehrlich explains, “what appears to be the IAEA’s greatest weakness has actually contributed to its success: While the promotional agenda of the IAEA bore risks, it also allowed the agency to facilitate diplomats and national experts coming together at the same table in pursuit of shared missions.”

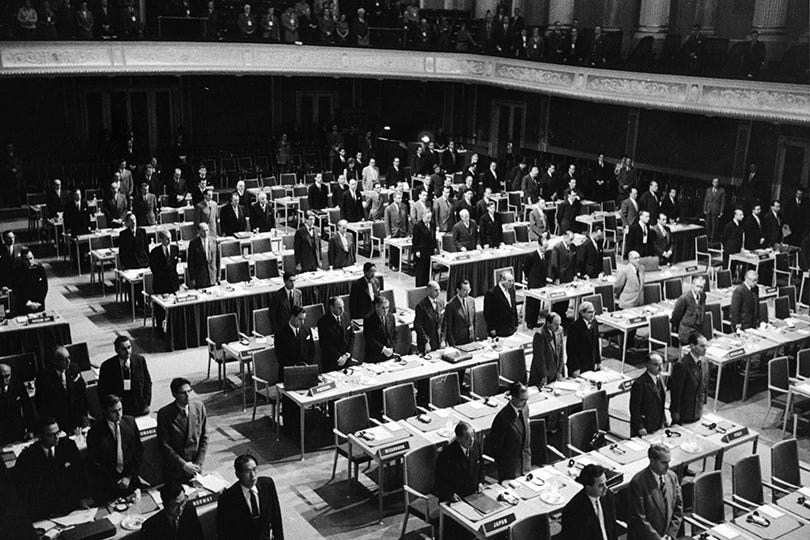

After introducing the reader to the risky and counterintuitive dual mandate, the book returns to the beginnings of the IAEA. In chapters one, two, and three, it traces the origins of the IAEA in the aftermath of the Second World War up to its formal creation in 1957. It starts with the infamous Acheson-Lilienthal report and Baruch Plan, named after US diplomat Bernard Baruch, that called for the establishment of an international Atomic Development Authority. This organisation, which would have “managerial control or ownership of all atomic energy activities potentially dangerous to world security” and the “power to control, inspect, and licence all other atomic activities”, was ultimately rejected by the USSR on the grounds that the United Nations was dominated by the United States and its allies in Western Europe.

During this portion of the book, Roehrlich considers Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace initiative and the acceptance of a new model of governance based on the idea of deterrence. Because total control could not be guaranteed, the book suggests that states organised around a compromise based on the introduction of inspectors who could act as a deterrent while maximising the effective scope of the agency.

Chapters four, five, six, and seven, detail the early years of the organisation as it grew in size and stature, the failures of safeguards evidenced by the 1974 atomic bomb test, the introduction of the Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1970, and what Roehrlich characterises as the ‘north-south’ tensions between nuclear haves and have-nots that surrounded the IAEA in the 1970s and 1980s.

Inspectors for Peace neatly ties together the defining moments of IAEA’s history, with the development of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, for example, connected to the early safeguard guidelines agreed by the IAEA in the 1960s. It demonstrates the evolution of the safeguarding programme over time, showing how the 1961 safeguards (which only applied to research and small power reactors and to materials placed voluntarily under IAEA safeguards) were superseded by the NPT whose ratification provided the organisation with the authority to routinely conduct on-the-ground inspections across the world.

The closing sections of the book focus on how the IAEA dealt with the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, especially with respect to the way in which the organisation’s leadership struggled with a public relations crisis that ‘put the whole of nuclear energy on trial’. Returning to the argument made in the opening few pages in the final chapter, Roehrlich proposes that the history of the IAEA is the history of the dual mandate. Fewer than 250 pages, the economical Inspectors for Peace reminds us that international governance is messy, fraught, and imperfect. Often, though, it is these imperfections that make it possible in the first place.

Thank you for posting this review. It sounds like a book worth reading. But it would have been nice if you had drawn out some parallels or lessons that might be applied from the IAEA's history to the current debates around an international governance body for AI. Perhaps you plan to do this in a subsequent post? Should any such governance body also have a dual mandate, for instance? (It might make it more palatable to the AI have-nots, for example, but then again it might pose similar proliferation risks.) What does the book say about the establishment of a talent pool necessary to staff such a body? And what does it say about the risks of having a governance body but one that is relatively ineffectual in the face of determined state efforts at proliferation and capability advancement? It would be great to try to apply the book's lessons and analogies, rather than simply summarize the book's content.