After millennia of supremacy, we await our demotion. You can detect the trembling.

It’s found in the anxious insistence that artificial intelligence isn’t truly intelligent. Or that using AI is a cheat, a perversity, a turf violation.

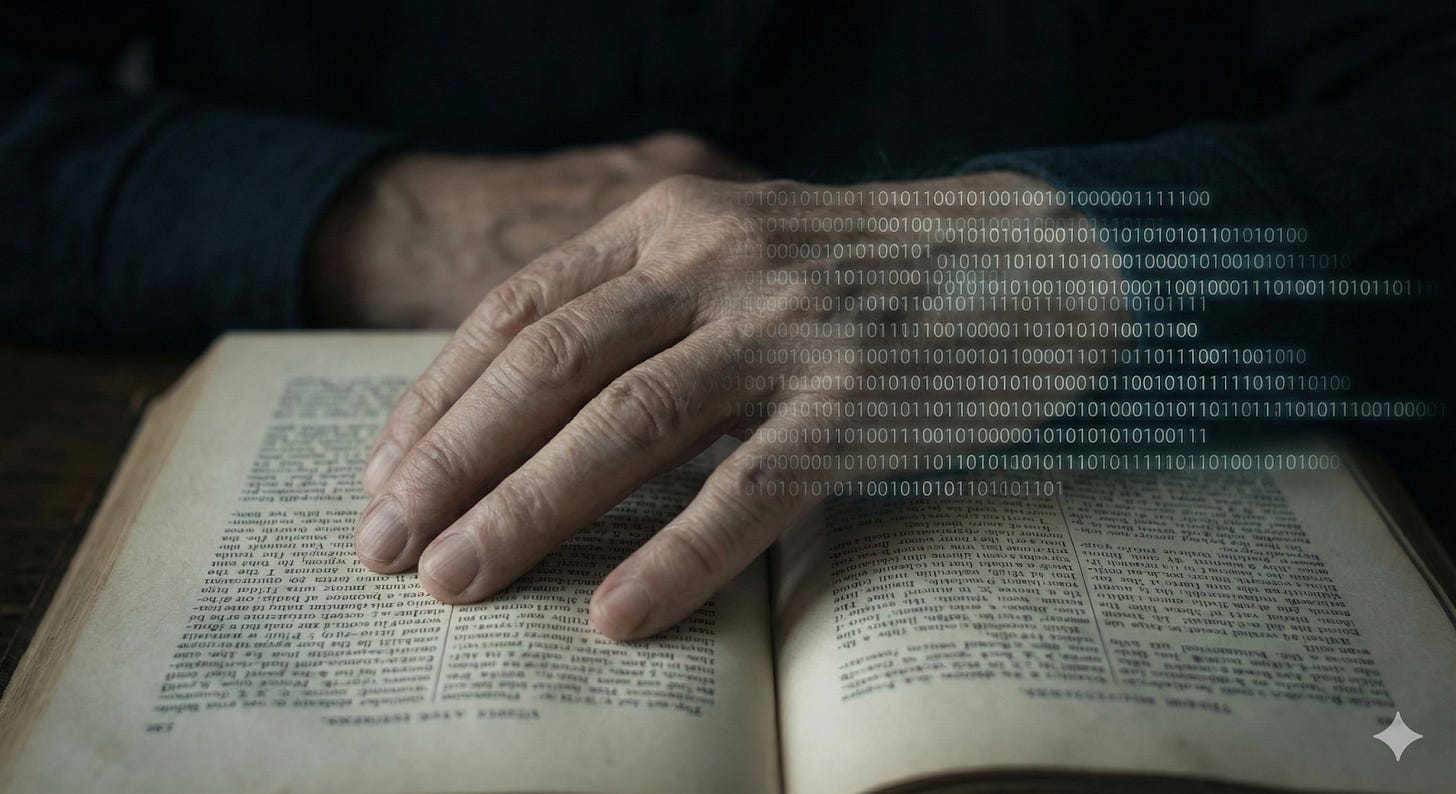

The trembling intensifies with a disturbing thought: What if those flares behind your eyes—the bursts of wit and the worry, the storyboards of memory, so many yearnings—what if everything was just computation? Because our “computers” are yesterday’s model, no updates available.

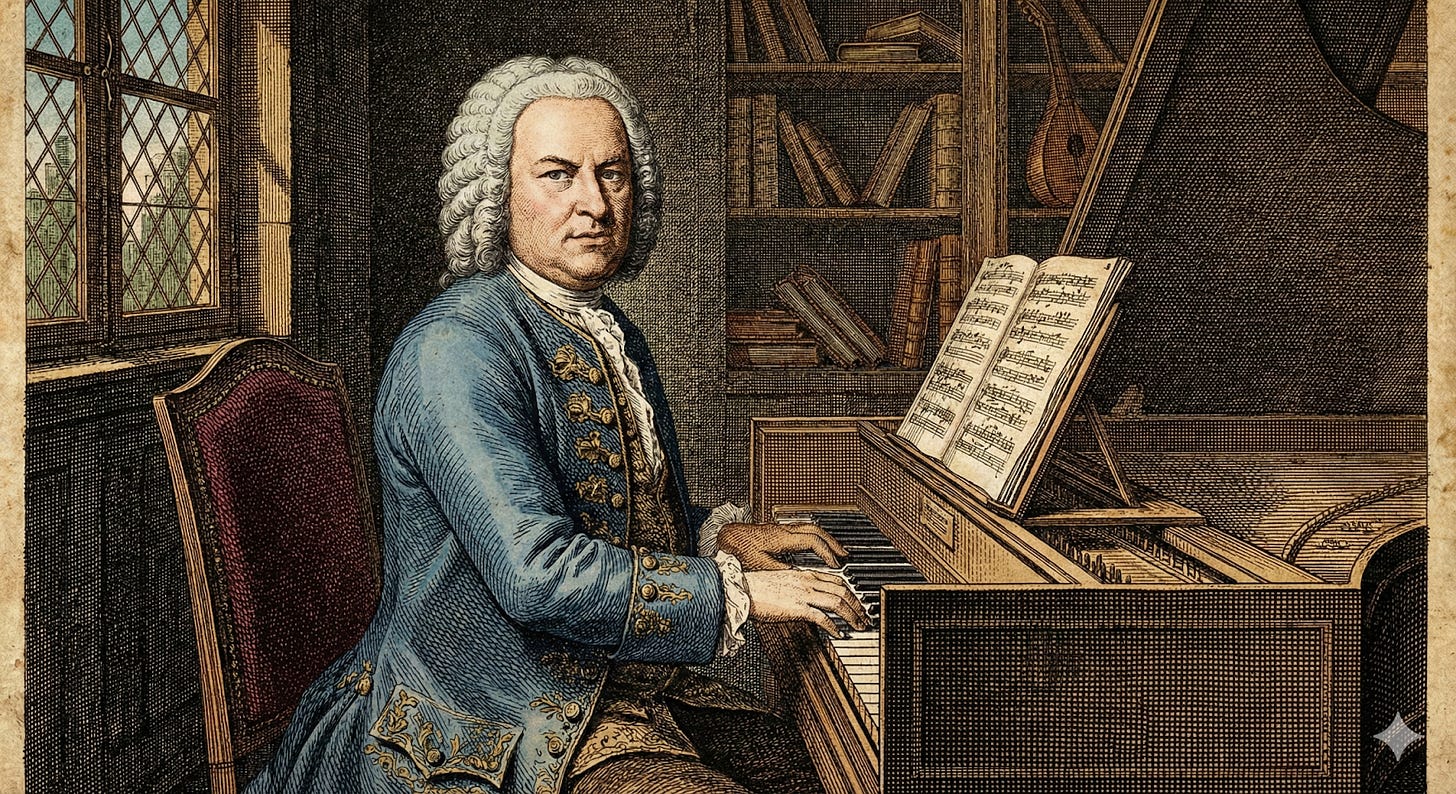

“I think about it practically all the time, every single day. And it overwhelms me and depresses me in a way that I haven’t been depressed for a very long time,” the cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter said recently. For much of his professional life, Hofstadter has contemplated the mind, writing a seminal 1979 book—Gödel, Escher, Bach—that looped through art, mathematics, and computation, inspiring a generation of nerds to work on artificial intelligence.

Their efforts moved faster than Hofstadter ever expected. Now, he spends his waning years observing the species wince toward redundancy. “I don’t want to say ‘deserving of being eclipsed.’ But it almost feels that way,” he says. “And rightly so, because we’re so imperfect, and so fallible.”

When humiliated, people corrode or explode. Often, both. But whom to blame? Will humans seek revenge on software, or data centers, or robots? We’ll depend on them all. More likely is that humans visit their wrath upon each other.

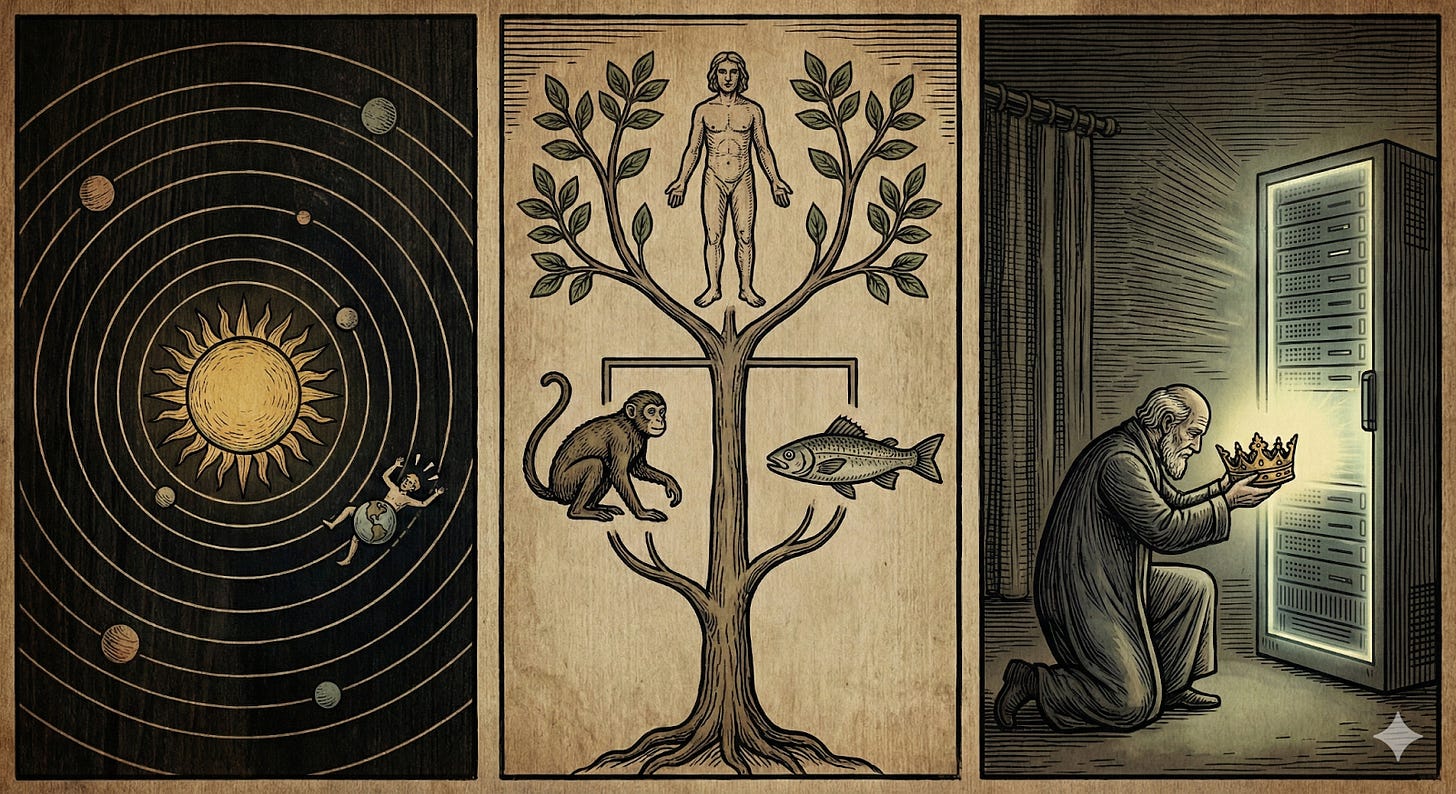

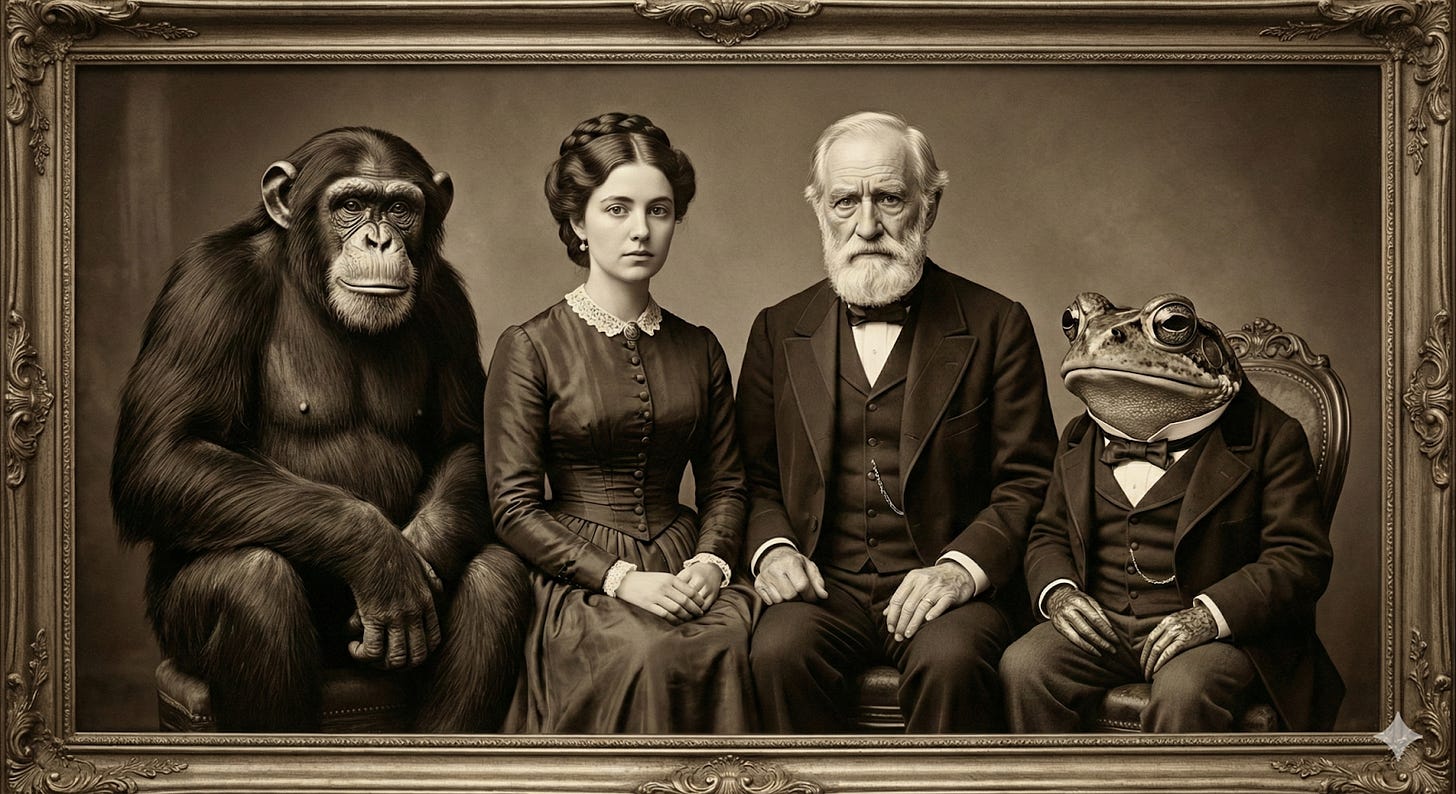

Freud said that science had delivered a series of blows to our collective ego, and an update to his narrative has bubbled up in recent years, with thinkers proposing AI as our new humbling. The first blow was Copernicus, revealing that humans were not the center of the universe. The second blow was Darwin, downgrading us from God’s chosen species to distant relatives of the toad, the centipede, and the hammer-headed bat.

Now comes the cognitive humiliation, when people are eliminated from every leaderboard. It’s a demotion that may haunt humanity, perhaps seeping into future conflicts.

Or maybe not. Maybe the notion of a species-level humiliation is just psychoanalytic melodrama. After all, people don’t share an ego. How could we synchronously plunge into the same bile?

Yet the past shows that groups can rage over perceived humiliation. History is spattered with such cases.

What Is Humiliation?

Your face shoved into the dirt, held there for all to see, no power to fight back. The word “humiliation” comes from the Latin for “earth,” as if your status had been stamped into the soil. Yet humiliation is not so readily rinsed away as dirt. In self-torture, the humiliated cast around for villains, aching for a way to expiate their anguish.

“To have thoughts of revenge without the strength or courage to execute them means to endure a chronic suffering, a poisoning of body and soul,” Nietzsche observed, adding elsewhere that “we attack not only to hurt a person, to conquer him, but also, perhaps, simply to become aware of our own strength.”

For early humans, humiliation may have meant catastrophic exclusion from the tribe, leading to starvation, rejection by mates, violent predation. So, we evolved a panicked drive to clamber up from the ground, even if it meant pulling down another person in our place.

As Joslyn Barnhart explains in The Consequences of Humiliation: Anger and Status in World Politics, “Humiliated states often seek to overcome their sense of helplessness by demonstrating efficacy through acts of aggression targeting third-party states that played no role in the original humiliating event.”

Hitler howled about German humiliation in the World War I surrender, and destroyed half of Europe to seek recompense. Osama bin Laden triggered a global war because of perceived Western humiliation of the Islamic world. Putin bemoaned the “degradation” of Russia at the hands of NATO after the Cold War to justify his 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

But those cases involved groups supposedly suffering disgrace at the hands of other groups. Could we feel humiliated by technology?

The first question is whether humans even identify as a species. The answer will probably fluctuate, given that we have many parts to our identity which become more or less salient according to context. Perhaps you identify by gender in a crowd of the opposite sex, but by your language when abroad. As Ronald Reagan once argued, a threat to all people could raise the salience of species identity.

“In our obsession with antagonisms of the moment, we often forget how much unites all the members of humanity,” the president said, in a 1987 speech at the United Nations. “I occasionally think how quickly our differences worldwide would vanish if we were facing an alien threat from outside this world.”

Humanity did face an alien threat recently: Covid. And our differences did vanish—briefly. But human unity dissolved when the pandemic affected groups in varying ways. This suggests that human solidarity requires not just a common threat but common consequences.

In short, AI humiliation may depend on how uniformly our species is downgraded, and who is raised up.

We, The Bottlenecks

Few researchers are studying what AI success could do to our collective self-esteem. Hints come from economists feverishly forecasting impacts on the job market. But psychologists (and politicians) ought to forecast what happens when the only animal to create guns has nothing much to do anymore.

“I’ve been suffering from fits of dread,” the philosopher Harvey Lederman wrote recently. “Does the coming automation of work foretell, as my fits seem to say, an irreparable loss of value in human life?” Lederman acknowledges that most jobs are lousy, but he can’t help grieving the demise of human pursuit. “We may be some of the last to enjoy this brief spell, before all exploration, all discovery, is done by fully automated sleds.”

When the philosopher Nick Bostrom envisaged troubling tech futures in his 2014 book Superintelligence, his ideas stirred the AI-safety movement. Lately, he has shifted from weird dystopias to weird utopias—specifically, what happens if automation makes us redundant.

In a future of “shallow redundancy,” he says in his 2024 book Deep Utopia: Life and Meaning in a Solved World, we become like aristocrats of yore, indulging in fancies, no longer dependent on what one does as a measure of what one is worth. Far more disconcerting is “deep redundancy,” when tech becomes so effective that human involvement only worsens each outcome.

Exercise might seem pointless if biotech offered a way to instantly make your body healthy and beautiful. Skipping the sweaty workout might not trouble you. But what if future humans would bungle child-rearing when compared with AI nannies, meaning that nurturing your offspring would worsen your kid’s life?

Primitive versions of this dilemma are nearing, like when human drivers endanger lives when compared with self-driving cars. “Human in the loop” could flip from a safety promise to a threat. Meritocracy would mean that no humans need apply.

The bookworm economist Tyler Cowen cites people as the great obstacle to explosive AI growth. During a public event, he pointed at the audience, smiling toward the human “bottlenecks” before him. “Here they are: bottleneck, bottleneck. Hi, good to see you! And some of you are terrified. You are going to be even bigger bottlenecks,” he said. “But my goodness, once it starts changing what the world looks like, there will be much more opposition. Not necessarily on what I’d call doomster grounds. But people [saying], like: ‘Hey, I see this has benefits, but I grew up, trained my kids to live in some other kind of world. I don’t want this!’ And that’s going to be a massive fight.”

The most agonizing aspect of our demotion could be social, once someone prefers a machine to you. You’re seeing precursors every time family members opt to gaze at a screen rather than gaze at you. We blame smartphones, and social media, and the adolescent brain.

But wait till your spouse jilts you for a personified agent. That rejection may feel unbearable: you can’t compete anymore. And once your loved ones prefer AI companions, you might seek them for yourself, spreading the social downgrade of our kind.

Already, the dread is becoming political, with odd alliances forming among right-wing politicos, liberal artsy types and religious traditionalists, united in horror at an imagined future of disempowered humanity, stripped of dignity, obsolete. You can imagine tomorrow’s political opportunist, eyeing a dejected crowd of humans before him, and thundering: “How dare they?!”

Will he mean the machines?

The Downwardly Mobile Species (Part I)

In prehistoric times, nothing seemed more unreachable than the night sky, specked with glinting dots and streaked with rare comets, passing in silent mystery. Humans pictured the supernatural looking down: we were the subjects in this bewildering story.

Religions codified the firmament above, mapping our world to the centerpoint. But Nicolaus Copernicus redrew the heavens with De revolutionibus orbium coelestium in 1543, plucking our globe from the core, and replacing it with the Sun.

“And new philosophy calls all in doubt,” the English poet John Donne said in “An Anatomy of the World,” written in 1611:

The element of fire is quite put out,

The sun is lost, and th’earth, and no man’s wit

Can well direct him where to look for it.

Science corrected an astronomical falsehood, but human confidence relies on falsehoods. “Tis all in pieces,” Donne wrote, “all coherence gone.”

The revised cosmos demoted each human into “a puny, irrelevant spectator,” the American philosopher Edwin A. Burtt wrote in 1925. “The gloriously romantic universe of Dante and Milton, that set no bounds to the imagination of man as it played over space and time, had now been swept away.”

The world that people had thought themselves living in—a world rich with colour and sound, redolent with fragrance, filled with gladness, love and beauty, speaking everywhere of purposive harmony and creative ideas—was crowded now into minute corners in the brains of scattered organic beings. The really important world outside was a world hard, cold, colourless, silent, and dead; a world of quantity, a world of mathematically computable motions in mechanical regularity.

The Church tried to snuff out the astronomical heresy, which challenged its claim as holder of truth. But suppression only fed into hostility from Northern Europe over the influence of Rome. In the bloody century after Copernicus, wars over religion and political control cost millions of European lives. It would be a wild distortion to suggest that a blow to human narcissism caused this. More plausible is that disruption of the cosmic hierarchy reverberated with the changing order on Earth.

And so the scientific revolution proceeded, with feats of mind illuminating more of the dark universe around us. People had greater reason than ever to admire our species. Inevitably, the scrutiny of science turned from the heavens to the humans.

“Man’s destiny was no longer determined from ‘above’ by a super-human wisdom and will, but from ‘below’ by the sub-human agency of glands, genes, atoms, or waves of probability. This shift of the locus of destiny was decisive,” Arthur Koestler wrote in his 1959 book The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe.

The Downwardly Mobile Species (Part II)

If Copernicus hurled humanity into orbit, Darwin deposited our species in an awkward family tree. Previously, the Western vision was of a great chain with God at the top, angels below, then humans, and finally the dimwitted beasts. The prospect of sharing more than a planet with our hairy former underlings proved too alarming for many to accept, provoking disputes about our relationship to nature that persist today.

For some, our new self-concept broadened moral consideration to include the natural world, motivating environmental protections, and the fight against animal cruelty. But another response was darker, with “survival of the fittest” twisted from a description of natural processes into a supposed mandate for the most inhuman of human drives: to dehumanize the vulnerable. Horrors followed, from colonial genocide, to the eugenics movement, to the Holocaust.

But again, you cannot ascribe such evils to a puncture in human vanity. A more reasonable claim is that the world lurches into periods of volatility, and the prevailing beliefs about human worth at those times will condition how we treat each other, and how conflicts unfold.

After the atrocities of World War II, our species set moral boundaries into law, seeking to universalize human rights. The spread of democracy and the free market too amounted to a veneration of human wisdom. But in the digital age, humanity seems to be losing confidence in humankind.

Faith in democracy falls. The Global Financial Crisis smashed public confidence in our governing systems. And the bewitching power of algorithms have become a constant lament.

Resist. Resign. Rewire.

When Alan Turing proposed his test of machine thinking, he foresaw that the notion would rattle people, and reviewed a list of likely objections, versions of which you hear today:

…that artificial intelligence could never genuinely be kind, or fall in love, or “enjoy strawberries and cream”

…that God gave only humans a soul

…that machines will never create anything truly original

What Turing called the “heads in the sand” objection is especially prevalent, with contemporary ostriches insisting that AI is a hype mirage, that it’s just next-token prediction, nothing but pattern-recognition, regurgitating human thoughts, that AI errors are proof of its worthlessness. (Human errors never lead to that conclusion.)

Plenty of AI hype does circulate. And deployment will be fitful: sometimes worryingly fast, sometimes frustratingly slow. An investment bubble could burst.

But the technology is amazing already, useful already—and we’ve hardly begun to figure out its uses. Meanwhile, AI dutifully hurdles more obstacles each month.

Who Are We?

In cautionary tales, humans who create artificial life always overlook a key trait. The golem of Jewish folklore was brought forth from clay but lacked smarts, so ran amok. Frankenstein’s monster missed out on looks, and never got over it. Pinocchio craved a human soul. As tech advanced, the missing trait updated, becoming human empathy, missing from all those immoral bots in everything from 2001: A Space Odyssey, to The Terminator, to The Matrix.

Such stories flattered humanity: among all creations, we alone enjoy the full complement of qualities. But lately, the narrative has updated again, with thinking machines now flickering with hints of greater humanity than the humans who employ them, from Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence, to Ex Machina, to the novel Klara and the Sun, by Kazuo Ishiguro.

It’s as if culture senses an anxiety about what technology might expose, not just demoting us cognitively but snuffing out any human exceptionalism. Unless we intend to boast of our frailties. Increasingly, we do.

“In a world where everything can be perfected, imperfection becomes a signal,” the head of Instagram, Adam Mosseri, wrote recently. “Rawness isn’t just aesthetic preference anymore—it’s proof. It’s defensive.”

Or as the Indian filmmaker Shakun Batra remarked in defense of human authorship over machine-generated scripts: “AI doesn’t have childhood trauma.”

At the AI frontier, another thought lurks, inverting Turing’s 1950 question. Not, “Can machines think?” But, “Do humans think?” More precisely, do we reason and comprehend uniquely, as we’ve presumed?

Machines compose music. They propose vacation itineraries. They’ll suggest how to talk to a moody teenager. Each additional AI capability is an implicit downgrade of us, a suggestion that maybe the human mind itself is just an information-processor.

Computer geeks have long muttered about this possibility. Philosophers debated it in thought-experiments. Cognitive scientists scrutinized our gray matter for clues.

But what approaches is a public dawning, forcing the culture to digest the indigestible, much as happened in previous eras, when people confronted the bizarre notion that our planet was another rock spinning around another star, or that our species was just another animal.

The third shocking revelation is upon us. Maybe it’s computation all the way down. Maybe there’s nothing soulful in neural substrates. What if we’re all just “meat computers”?

How We’ll React

You can predict three possible responses to our humbling: Resist, Resign, or Rewire.

Resist: Psychological resistance will manifest as political resistance. The question is how ideology and parties evolve around AI humiliation. Resistance movements will face a persistent challenge: industrial dynamics will keep driving this technology forward. Any country that curbs innovation fears that its rivals will win. The most aggressive branches of resist may seek to avenge their perceived humiliation. The question is not only whom they blame or how they exact revenge. It’s what, realistically, they expect to regain.

Resign: Some will reframe their view of humanity to accept the humbling. The optimistic version is that people discover freedom in their new humility, pursuing what improves life rather than grinding under the force of insatiable ambition. In short, we cede the battle for supremacy but flourish. A more pessimistic version is that losing faith in our species’ unique worth makes people value others less: when humanness is no longer special, perhaps human rights aren’t either.

Rewire: This may be the most widespread response. People accept that the downgrade happened, yet their egos are never tamed, much as chess remains popular long after machines defeated us. A more literal “rewiring” is transhumanism, with technology incorporated into our bodies, even altering our genetic future. Conspiracists picture shadowy elites consolidating power by becoming a tech-altered superspecies, leaving behind “legacy humans.” A more plausible scenario is biotech gradually elevating human cognitive capacity, much as today’s medical tech remedies physical frailties, from hearing aids to the replacement knee.

The Next Quest

If humankind suffered humiliation before, we weathered it. After Copernicus and Darwin, we still took pride in ourselves. Indeed, we celebrated human accomplishments more than ever, from Bach to Escher to Gödel. And that pride propelled us into this strange time, when human greatness may design human demotion.

Policymakers need to think about more than the economic shock. The psychological shock could be exorbitant if we are chased from the kitchen like pesky children, and told to go busy ourselves elsewhere.

Our downgrade doesn’t necessarily mean conflict. But it could change how future conflicts unfold, especially if we value humans differently, or seek relief from our humiliation by shoving others into the dirt.

Much depends on how we redefine our species. Whether humans really are nothing but computational machines may matter less than whether people feel this way.

But what will make us exceptional? Today’s responses are often vague and circular: that humans are better at doing human things. That is a precarious claim. As intelligent machines grow more adept, few people will pay a human-premium for a worse outcome.

Unless there really are qualities both valuable and uniquely ours that nothing can supplant. Finding these may be our new quest.