In this essay, Julian Jacobs writes about the history of US public worker retraining programmes, their efficacy, and how they might fare as AI diffuses throughout the economy.

When asked to reflect on how AI may affect society, people frequently rate the loss of their job as their top concern. Such worries are not new. During the Industrial Revolution, the Luddites smashed textile machines and fought with mill owners, even if their demands were more nuanced than is often ascribed. At the turn of the 20th century, public administrators overseeing the US economy feared how new kinds of glassware and steel might impact workers.

Such fears are understandable. Jobs, particularly the skilled trades that are often most vulnerable to automation, can provide financial independence and feelings of status, purpose, and community. This is of course not true for all jobs, all the time. In his seminal book Working, Studs Terkel observed that many people feel their jobs are defined by a lack of meaning, as well as an intense disconnectedness, fatigue, and a droning anxiety about wasting their lives. But surveys of today’s employees, at least in the West, suggest that a majority are relatively satisfied with their job and that as many as 50%, or more, would want to continue working even if they did not need the money.

1. Will we need retraining to respond to AI?

When new technologies disrupted employment in the past, they typically led to an increase in aggregate employment, albeit not always immediately. This was true with the steam engine and spinning jenny during the Industrial Revolution, and with industrial robots and digitisation in the 20th Century. However, in the US, where labor unionisation has been mostly declining, these latter technologies also widened income and, especially, wealth inequalities. This was mainly due to two dynamics - the extent of which economists continue to dispute.

First, the technologies increased productivity and economic growth, but a growing share of this expanding pie went to capital owners, especially those with a significant ownership stake in fast-growing enterprises. Labour’s share, once inflation was accounted for, declined. In 2022, according to the economist Loukas Karabarbounis, the share of income going to labor in the US hit its lowest point since the Great Depression, at just under 60% of national income.

Second, the technologies complemented people with certain skills while displacing others - what economists refer to as ‘skill-based technological change’. Digitisation and industrial robots automated middle-wage occupations such as clerks, bookkeepers, and assembly line workers, while enabling high-paying roles for software engineers, roboticists and data analysts. These new roles also fostered demand for lower-wage roles, including to provide services to higher earners, for example in the retail, healthcare, food service or personal grooming sectors. These two trends made the labour market more polarised, as workers who lost their jobs or were unable to benefit from new technologies struggled to move into higher-wage work. If we expect AI’s impacts to be similar, this could provide a rationale for governments to fund large retraining programmes to help people retain their jobs and move into higher-wage roles.

Will AI’s effects be similar? We don’t know. Some efforts to address this question break jobs down into bundles of tasks and evaluate AI’s ability to perform them, now and in the future. These evaluations cover a wide range of jobs and tasks, but they don’t tell us whether organisations that hire people to do these tasks are investing in AI, or changing their hiring. Other studies do assess the impact of AI on real-world employment outcomes, for example on freelance employment, but only cover a small share of the labour market. No assessments yet give us breadth and depth.

In the near-term, the employees at greatest risk from AI are likely those that work in, or would like to work in, occupations where tasks are currently performed (almost) entirely on a computer. And where some degree of human error is already common and not catastrophic. This may include graduates aspiring to work in consultancies, legal firms or content agencies or the large number of people who work in remote customer service roles. If new kinds of AI-enabled robots become more capable and cheap, then other kinds of roles, for example in warehouses, could be at risk.

If AI starts to cause people in these roles to lose their jobs en masse, we can expect loud calls for new public retraining programmes. The idea that the government should help to retrain people in response to new technologies, trade shifts or other ‘shocks’ is ubiquitous in policy briefs, consulting reports, and academic research, including on AI. But, these reports typically don’t specify what an AI-induced retraining programme should look like, who should do it, and what lessons, if any, we should draw from past efforts.

In the remainder of this essay, I trace the history of US public retraining programmes and their impacts. In short, I find little evidence that they have been effective. In future essays, I hope to consider lessons from private retraining programmes and other countries.

2. A brief history of US public retraining programmes

In 1933, as the Great Depression reached its darkest moments, President Roosevelt signed the Wagner-Peyser Act, creating the United States Employment Services, a new national network of offices to help the ~25% of the labour force that was out of work. Their retraining offering was rudimentary but provided a foundation to build from. Since then, retraining has become an integral ‘Active Labour Market Policy’ in the US and beyond. If passive labour market policies, like unemployment insurance, aim to provide a safety net for the unemployed, active policies like retraining and job search assistance aim to provide a ladder back into stable work.

In 1962, John F Kennedy signed the Manpower Development and Training Act, the first federal retraining programme to operate at scale. Over the next decade, it retrained 1.9m people to navigate the ‘constantly changing economy’. For men, this typically meant retraining as machine shop workers, auto mechanics, and welders. For women, clerical and administrative roles. In 1973, Richard Nixon replaced the MDTA with the short-lived Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, which focussed on getting low-income individuals, the long-term unemployed, and students into subsidised, entry-level jobs in public sector agencies and nonprofits.

CETA began a process of decentralising US public retraining, putting decisions about how to run the programmes into the hands of cities and states, rather than the federal government. In 1982, the Reagan administration accelerated this further, when it passed the Job Training Partnership Act. In line with Reaganomics, the JPTA aimed to further empower local organisations to deliver retraining and boost private sector employment. To do so, it established Private Industry Councils, with representatives from local businesses, to help direct and supervise the programmes. It also tightly means-tested participants, with the vast majority coming from low-income or “hard to serve" backgrounds, which included people with disabilities, the homeless, offenders, welfare recipients, and out-of-school youth. The training focussed on cultivating basic skills, such as remedial reading and maths, ‘work habits’, such as punctuality and résumé writing, and short, entry-level courses for clerical, services or trades work.

As I expand on below, today the JPTA is typically viewed as a policy failure. In 1998, Bill Clinton replaced it with the Workforce Investment Act, which significantly widened the criteria for participation, making retraining available to anybody who wanted it, while giving low-income and disadvantaged people priority. If the JTPA was essentially a poverty reduction scheme, the WIA aspired to become a universal employment service, including for displaced middle-income workers, when budgets allowed. The WIA also sought to prepare individuals for a more fluid labour market. Unlike JPTA and CETA, which offered participants little choice, the WIA provided individuals with “individual training accounts” so that they could (at least in theory) choose the skills and sectors to invest their time in, once they had completed some general training.

In 2014, Barack Obama replaced the WIA with the more streamlined Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act, which today provides most US federally-funded retraining. The WIOA allows participants to directly participate in their preferred retraining services, without the need to first participate in more general training. It also allows regions to offer more locally-relevant retraining and has tried to increase accountability, by requiring more third-party evaluations.

Every year, approximately ~500,000 participants take part in the WIOA’s ‘Adult’ and ‘Dislocated Worker’ streams, of whom ~200,000 receive training vouchers, at a cost of ~$500m. As noted by David Deming and colleagues, this is a relatively low figure, when one considers that the US government spends 25bn a year on Pell Grants for undergraduate education. Most WIOA participants are low-income, but their profiles vary. For example, most of those on the ‘Adult’ stream are below or near the poverty line, with limited education or employment experience. In contrast, most of those on the “Dislocated Worker’ stream have lost stable employment, for example in manufacturing, and are more likely to be older with more substantial work experience. Although not mandatory, people who receive welfare and public assistance are encouraged to apply and make up approximately one third of WIOA adult participants, according to a 2022 evaluation.

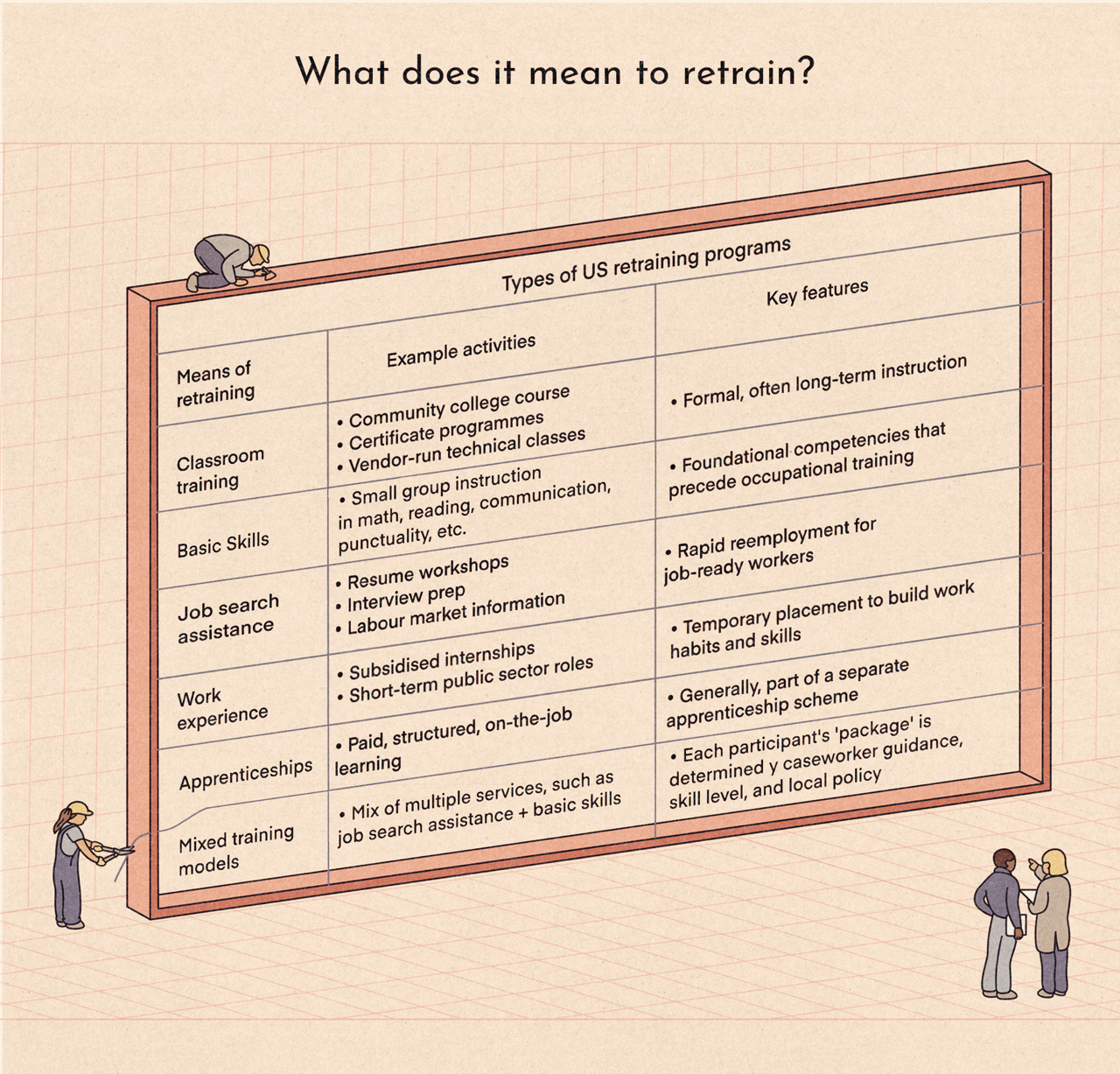

The skills that WIOA retraining programmes impart and their method of instruction vary considerably across US states, owing to differences in the capacity of local retraining providers (who must bid for federal funding), employer needs, and political considerations, which can override more objective readings of labour demand. The result is a patchwork. In 2015, Burt Barnow and Jeffrey Smith distinguished between different types of retraining, from small group sessions focussed on basic skills to subsidised apprenticeships. In the early days of the Clinton era Workforce Investment Act, 47% of participants enrolled in formal, classroom retraining programmes, but this figure ranged widely across states, from 14-96%. According to data from 2023-24, less than 10% of WIOA training involved paid on-the-job training, and just 2% involved apprenticeships.

Summing together, over the last 80 years, we have seen a steady evolution in US public retraining, from more centralised, New Deal-style programmes to more decentralized efforts targeting local private sector employers. The goal has shifted from addressing widespread unemployment to reducing poverty and back towards a more universal employment service that integrates retraining with other policies, such as job search support.

We can expect further changes. The Trump Administration has proposed merging the WIOA’s programs into a single funding stream titled ‘Make America Skilled Again,’ which may result in a significant funding cut and replace much of today's federally funded training with apprenticeships. However, the proposal will likely be altered significantly as Congress deliberates on its details. So the future of US federal retraining, and how it may respond to AI, is still very much to be determined.

3. Does public retraining work? The evidence base

Consider the hypothetical example of ‘Tony’, who used to be employed at a mid-sized auto parts manufacturing plant in Ohio, until his employer steadily introduced a wave of industrial robots. As documented by Thomas Phillippon in The Great Reversal, many US localities are dominated by a handful of ‘good’ employers. The absence of alternative options reduces worker bargaining power and wages. It also makes layoffs more challenging as employees like Tony must compete against many others, most of whom also lack transferable skills to pursue other roles.

After a prolonged job search, Tony enters a Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act retraining program, run by his local American Job Centre. Owing to his low-income status, he is given priority. Upon arrival, the Centre screens Tony to see if he qualifies for the Dislocated Worker stream. Once confirmed, he is asked to participate in maths, problem-solving, and reading assessments, as well as an aptitude test. From there, a counsellor reviews labour market data and recognising Tony’s background in the auto trade, proposes a variety of skilled trades. She also proposes the opportunity to reskill into a new sector, like medical assistance. If Tony is under pressure to return to work quickly, he may move directly to job search assistance and on-the-job retraining. Alternatively, he may pursue longer classroom retraining at a community college or technical school. If all goes well, he will have regular meetings with his counsellor, participate in soft skills workshops and networking events, and will land a secure new job, with regular progress check-ins.

In reality, successful examples like Tony are rare. In 2016, the year of Donald Trump’s first election, David Autor, David Dorn & Gordon Hanson published ‘The China Shock’ - arguably the most impactful US economics paper of the past decade. The study demonstrated that, since the 1990s, import competition from China had devastated large parts of the American workforce, particularly regions focussed on manufacturing textiles, furniture, toys and other light goods. The shock reverberated across communities, igniting brain drain and depressing economic and social prospects for a generation. Meanwhile, other sectors, regions and employees benefited from cheaper imports.

The China Shock, and the wider technology-based automation that was occurring in these sectors, led to a glut of displaced workers and a stream of youth in search of alternative employment opportunities. This was the sort of challenge that the Clinton-era Workforce Investment Act and the Obama-era Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act were designed to address. However, Autor and colleagues showed that many displaced employees either failed to find employment or were forced to take up new roles in the service sector, for example as cashiers or security guards, that were often less-skilled, lower-paid and less rewarding.

These findings chime with the more formal evidence base on US public retraining programmes. To evaluate retraining programmes, researchers expend considerable effort to track key variables, including the proportion of participants who find work shortly after exiting, the proportion who remain employed for at least six months, and their average earnings. In general, researchers have failed to show any statistically significant benefit on these outcomes.

Teasing out why - and what this means for future retraining programmes, including for AI - is difficult. One key challenge is non-random selection. The population that takes part in retraining is not representative of the wider population of people who have been displaced. This means that we do not know the extent to which participants’ subsequent labour market outcomes are due to the impact of the retraining programme (or lack thereof), or other characteristics that are more common among participants, such as a willingness to take part in retraining in the first place.

To address this issue, researchers use quasi-experiments that aim to approximate randomised controlled trials by matching a group of people that did participate in public retraining programmes - say 10,000 middle-aged men from rural districts - with a similar group that didn’t. However, to do this well, researchers need to know what characteristics are most relevant to future labour market outcomes - prior education?, proximity to a nearby city? - so that they can control them. And many potentially important social or psychological characteristics are impossible to reliably capture in datasets. On top of this, researchers must try to account for the huge variance in the focus, format, and resources of different states’ programmes. As a result, some researchers conclude that it is impossible to make reliable causal claims about why public retraining is, or isn’t effective.

The evidence that does exist provides cause for skepticism. For example, a National Study to evaluate the Reagan-era Job Training Partnership Act, involved a genuine randomised controlled trial that ran from 1987 to 1992, with a representative sample of more than 20,000 participants. It found no statistically significant improvement in employment rates, employment duration, or earnings. In 2019, a 10-year evaluation of the Workforce Investment Act, and the Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act found that, while intensive one-on-one career counselling did improve employment and earnings outcomes, the programme’s retraining streams did not.

As of 2023, the most recent data available, 70% of participants in WIOA were employed in the 2nd and 4th quarters after finishing their retraining programmes. But these outcomes are not compared to a control group, so we don't know if, or to what extent, WIOA is truly improving them. Even when WIOA retraining is helping people find jobs, research by David Deming and colleagues suggests that ~40% of participants are being trained into ‘low-wage’ support roles, particularly in the healthcare sector. The most common roles, such as nursing assistants, come with an annual salary of less than $25,000. Demand for these roles is high, which explains the WIOA’s focus on them, but they often offer little scope for career growth.

There is even evidence that some retraining programmes may hurt participants. For example, a 2012 evaluation of the US Trade Adjustment Assistance programme, which provides retraining to workers displaced by outsourcing and trade, found that participants had lower employment rates in the two years after they were laid off, compared to similar workers who did not participate, potentially due to the opportunity cost of not being able to apply for more immediate work opportunities. Even four years after losing their job, TAA participants were underemployed and earned slightly less, compared to non- participants.

4. Why does retraining fail?

In the absence of clear causal evidence, researchers are left to speculate as to why US public retraining programmes have underwhelmed.

A first challenge relates to the participants and their ability and willingness to take part. Some potential participants may avoid retraining, or drop out, due to the costs involved, which range from transport to arranging childcare - single parents are over-represented among participants. These cost pressures are particularly strong for candidates who are still in work but at risk of losing their jobs. For those with little savings, even the offer of a payment to take part in retraining, may be insufficient.

In other instances, there may be a mismatch between the training and career paths on offer and what candidates are interested in, or capable of. For example, older workers, often close to retirement, have been overrepresented in some of the jobs displaced by digitisation and may be less enticed by retraining into a brand new sector. Retraining participants are also disproportionately likely to have been homeless, an offender, or to lack the basic skills that longer classroom training requires.

All participants may be bewildered by the choice on the offer. As David Deming and colleagues note, the WIOA funds ~7,000 Eligible Training Providers and ~75,000 programmes, in more than 700 occupational fields. Although it aspires to provide ‘informed consumer choice’, via its voucher system, the websites describing different programmes can quickly overwhelm candidates, while failing to provide the comparable programme information and performance data that people need.

A second challenge relates to training providers and their ability to offer a high-quality service that is well-curated to local employers’ needs. Experts note huge variance in the quality and format of local training providers, but with such a large number of providers, the evidence base does not allow us to reliably tease out the good from the bad. Training providers also struggle with the bureaucracy that public programmes entail and the challenge of ensuring that the skills they provide are useful in an ever more specialised economy, where many skills are not easily transferable. Providers also need to look beyond the current labour market and anticipate future skills demands - a task that has always been hard, if not impossible, and which AI is now exacerbating.

A final challenge is that there may simply not be enough skilled jobs for people to retrain into. The typical question for workers looking to retrain is not: “How do I find employment?”, but rather “How do I get a more secure, better paid job?” Past technologies did not increase the aggregate unemployment rate, but there is evidence that they did lead to short to medium-term reduction in the number of ‘skilled’ occupations for workers to retrain into. In the AI era, similar challenges could emerge if, for example, new university graduates were unable to find the kind of role, or career path, they expected.

Retraining & AI: Four ideas

What does this mean for concerns about AI? At a minimum, we should avoid assuming that public retraining programmes will be a useful response. The baseline hypothesis is probably that they won’t. However, there should be ways to make them more useful.

Here are four ideas:

1. Develop better labour market projections

There is vast uncertainty about how quickly AI capabilities will develop, diffuse through the economy, and affect workers. This uncertainty will not disappear any time soon. But AI labs and policymakers could make it easier for retraining providers to understand the jobs that may get displaced, prove more resilient, or emerge. At the moment the US Bureau of Labour Statistics provides high-level forecasts for demand for different occupations. AI labs could work with policymakers and researchers to develop much richer and more granular forecasts that draw on, among others, the latest AI capability evaluations; insights from how users are querying LLMs, online job postings, and government surveys of employers and graduates.

2. Experiment with new retraining approaches

Almost 80% of Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act retraining takes place fully in-person, while just 7% takes place fully online. This creates barriers for people in more remote regions and hinders innovation. It will be difficult to usefully change this, because delivering high-quality online education is hard. As the scholar Mary Burns noted in an evidence review for UNESCO, “few innovations have generated such excitement and idealism - and such disappointment and cynicism - as (digital) technology in education.”

But now is the time to experiment. Education providers are learning from their failures, such as the early Massive Open Online Courses that crudely transposed offline learning content. Some providers are shifting to hybrid formats, while others are developing targeted micro-credential courses. In the AI community, labs are training large language models, and the tutors based on them, to be more ‘pedagogically inspired’, while educators and students are using multimodal AI to personalise learning materials to the language, format, or substance they want. Against this backdrop, there should be opportunities to design AI-enabled retraining programmes that are more dynamic and better able to respond to labour market needs. Another goal of such retraining, at least for some participants, could be on how to use AI systems most effectively.

3. Collate better evidence about what works

At the moment, we have little evidence about what works, or doesn’t, with respect to public retraining programmes. This is particularly true for training provided to workers displaced by new technologies. Future evaluations should target this group, with a focus on those affected by AI, and understand how outcomes are affected by factors such as programme type, age, gender, geography, prior education, and existing skills. This will require better data collection by public sector institutions, with a focus on RCT-style evaluations, but also smaller-scale experiments that academics or companies could run, with standardised measures to harmonise the two.

One area to explore is the nascent positive evidence on training programmes that are co-designed with employers, with specific sectors in mind. Some RCTs in this area show positive effects on earnings and employment, but they are small, typically including a few thousand people, and we do not know if they will generalise across geographies and sectors.

4. Consider goals beyond employment

Finally, it may be time to reevaluate whether ‘work’ should remain the central way to measure a person’s economic contributions and the central goal of any retraining programme. As Tom Rachman wrote in a recent essay: educational policy tends to tinker with the ‘What’ of learning (curriculum) and fret about the ‘How’ (methods). But it’s the Why that demands its boldest recalibration since the Enlightenment.

In theory, education can serve many functions, from boosting an individual’s agency to promoting national unity and assimilation. But preparing students for a career has come to dominate both retraining and broader education. If scenarios where AI has more dramatic economic effects materialise, we need to think about what other knowledge, skills and values people will need to navigate this transition, and the other ways that they can contribute to society. For example, future training programmes could include best practices on how to use AI agents, or how to improve community life and ward against atomization. This more flexible understanding of ‘work’ and ‘training’ could give us a better chance of navigating the AI economic transition in a way that preserves worker livelihoods, opportunity, and dignity.

I would like to acknowledge and thank Burt Barnow for his guidance and contributions in developing this essay. Thank you to Venus Krier for the illustrations contained in this piece.

This was a super interesting read. Thanks Julian!

Thanks for this Julian. I loved the point about Studs Terkel finding people felt a greater lack of meaning in their jobs in the 1950s, especially in light of Keynes's pro-leisure essay 'The Economic Opportunities of our Grandchildren'.

I also agree that AI could be an opportunity to improve the quality of re-training. I'd be interested to know what Multiverse argue about this and if there are any studies into their approach as I gather they've been quite successful and mainly do online learning. But I'm also animated by the David Autor essay from 2024 about how mid-skilled workers can use AI to upskill, which I feel compliments your piece.